Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 1)

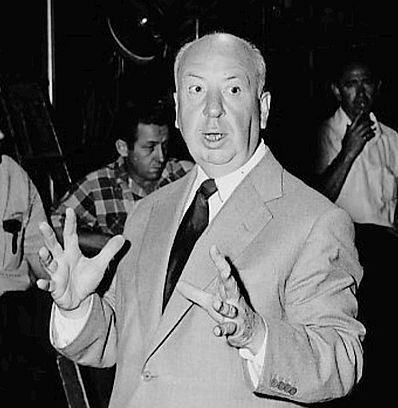

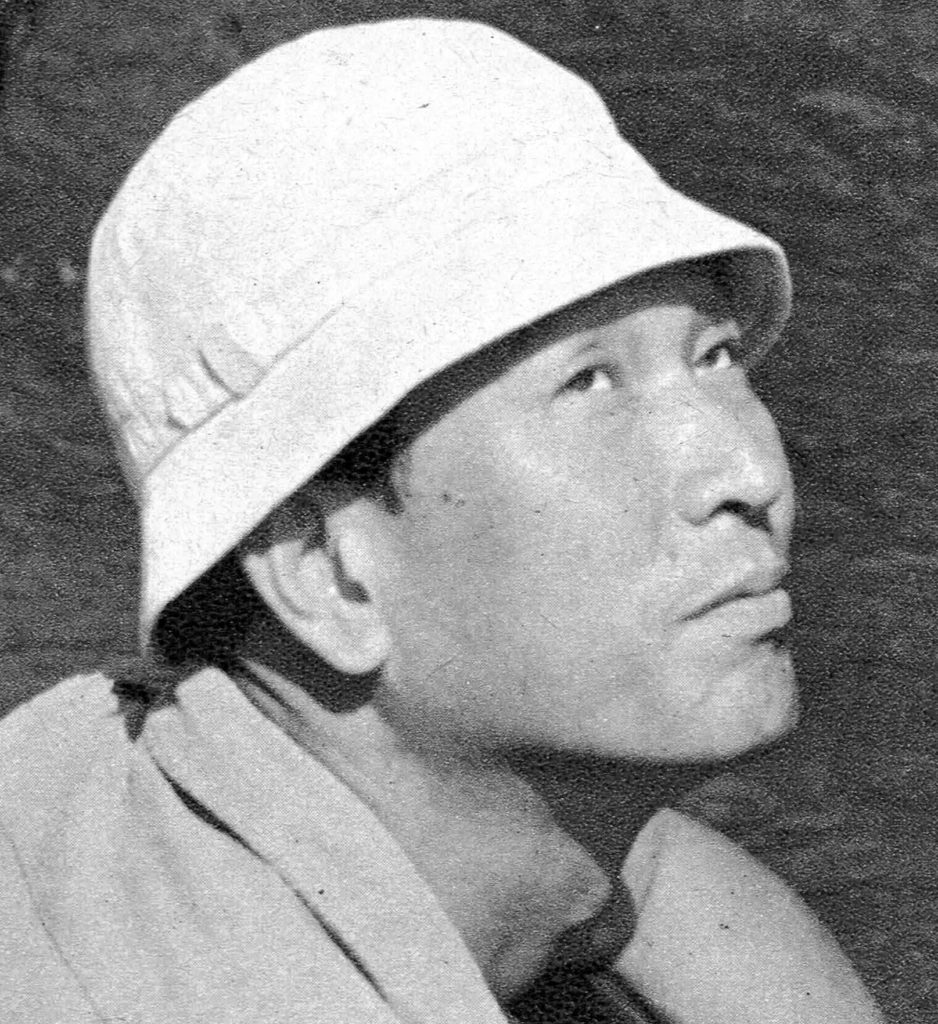

It has often been claimed that Uchida’s work lacks consistent themes, such as can be traced in the work of famous European and American directors who are universally accepted as auteurs. Examples would be John Ford’s concern with the disappearance of the American frontier and with outsiders who can’t fit into the new order, Jean Renoir’s preoccupation with the subtleties of class distinctions, Orson Welles’ obsession with illusion and decay, or Hitchcock’s fascination with the “transference of guilt” from one character to another.

The claim that Uchida’s work contains no comparable themes appears to be an attempt to deny him the status of a cinematic author, or at least as one important enough to rank with the top tier of directors. Whatever the motive, this argument seems to me completely wrong. Here are just six of the recurring, indeed obsessive, themes in Uchida’s work that I’ve been able to identify from the writings of others and from my own viewing.

The Bonded Adversaries – This theme involves two characters whose oppositional relationship creates a paradoxically close – almost inseparable – bond between them. (Alexander Jacoby was apparently the first to identify this recurring motif in Uchida’s films.)1 The characters need not be enemies, but their relationship must be of a sort in which each one’s need to dominate, and even destroy, the other takes precedent over any fellow feeling. Examples of films in which this theme is present are: Police Officer, Earth, A Hole of My Own Making, The Sword in the Moonlight trilogy, The Outsiders, Hero of the Red-Light District, the Miyamoto Musashi series, Swords of Death and, especially, A Fugitive from the Past.

The Sudden Eruption of Violence – This theme is easy to miss because of the violence that is inherently part of the samurai and crime genres in which Uchida frequently worked. In this dramatic model, the contradictions inherent in the social order gradually build up over the course of the narrative until the tension can only be released through a paroxysm of violence. Craig Watts, in his groundbreaking article about Uchida, not only pointed out this theme, but connected it to Mao Tse-Tung’s Theory of Contradiction that the director absorbed during his sojourn in China. Examples of films containing this theme are: A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji, The Outsiders, A Fugitive from the Past, A Tale of Two Yakuza and, most memorably, Hero of the Red-Light District.

Prostitution as Metaphor – This seems to be a theme exclusive to the films of the postwar period, though so many of Uchida’s prewar films are missing that it’s hard to say with certainty. The prostitution of a female character is seen as symbolic of the exploitation of the poor and vulnerable under an unjust social order. (This order need not be a capitalist one: the same is also shown to be true of feudal Japan.) The attempt of the woman to transcend her lot will (almost) invariably end in disaster. Examples are: A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji, Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka, Hero of the Red-Light District and A Fugitive from the Past.

The Wicked Weapon – Occasionally, the weapon a character wields can take on a life of its own, changing his nature or, more precisely, bringing out a side of his personality that he had attempted to suppress. Examples are: A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji, Hero of the Red-Light District, The Master Spearman, and, perhaps, both the Sword in the Moonlight trilogy and the Miyamoto Musashi series.

The Liberating Power of Madness – When an Uchida hero goes insane, he sometimes experiences the loss of reason as a paradoxical release from an intolerable reality. The devastating implication is that the social order is so noxious and stupid and unjust that derangement is actually preferable to sanity. Some examples are Unending Advance, Hero of the Red-Light District, The Master Spearman and (of course) The Mad Fox.

The Inexorability of Karma – This may be the artist’s most important theme because the guilt of his heroes, however ambiguous it may be, always requires some form of atonement. Some examples are Police Officer, The Horse Boy, the Sword in the Moonlight trilogy, the Miyamoto Musashi series and (most hauntingly) A Fugitive from the Past.

Good question… and there’s no simple answer to it. Many, many of his films from the prewar era no longer exist. Yet for other directors of Uchida’s generation (for example, Ozu), their prewar legacy of surviving films is quite extensive. The paucity of Uchida’s early films may have to do with the studio, Nikkatsu, for which he mostly worked in that era. (It’s significant that one of two surviving silent features by Uchida is Police Officer, which was made not for Nikkatsu, but for a minor studio, Shinko.) The loss of all this celluloid may not have been the studio’s fault, as a great deal of film (as well as other things and people) were destroyed by the Allied bombing in World War II. But it’s equally possible that many if not most of the negatives and prints of Uchida’s Nikkatsu films were simply neglected and left to decay, or else deliberately destroyed for their silver nitrate content.

For the postwar films, the issue is more complicated, since all the Uchida films of that period – except for A Fugitive From the Past, which was partly butchered by the studio – survive intact. Uchida’s postwar “home” studio, Toei, was, of all the six major studios of that later era – the “Golden Age” – the one least concerned with international prestige. All the evidence suggests that Uchida was considered by both the public and the industry as that studio’s master filmmaker. Yet its executives felt no compulsion to export his work, particularly since the foreign market for Japanese films represented only a tiny fraction of the domestic market, and there was no more bottom-line-oriented major studio than Toei.

To be fair, the studio did send The Horse Boy to compete at the Berlin Film Festival and The Mad Fox to the Venice festival, but neither of these two very different films was well-received by European critics or audiences. The executives at Toei may simply have concluded that the West would never really get Uchida.

Finally, unlike the Big Three Japanese directors – Kurosawa, Mizoguchi and Ozu – Uchida has no brand: that is, there is no easily-identifiable style and subject matter characteristic of this filmmaker. So, in a sense, Uchida’s extraordinary versatility has worked, and continues to work, against him as far as his international reputation is concerned. And that reputation, such as it is, has been kept alive mostly by very occasional retrospectives, such as the one held at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in 2016 – and by fervent fans sharing DVDs and crumbs of information via the Internet.

Dedicated film fans may be understandably skeptical about my claims for Uchida’s greatness. Their general assumption may be that, since they have never even heard of Uchida, he can’t be a real film master, or if so, he must be a minor master at best. I’ve read some commentators who damn Uchida with faint praise by calling him a great “genre” filmmaker, implying that he could only successfully make a certain kind of movie, such as the samurai epic. It’s true that he was a master of the samurai film in the postwar era, but he was never defined by that genre, any more than John Ford was defined by the Western.

I know I’m probably making too much of a perceived tendency by some English-language commentators to condescend to this filmmaker. And I would never deny that among the director’s surviving works are some films that are minor by any standard (though almost all are entertaining and well-crafted). But my point is that, if Uchida is a minor moviemaker, Japanese critics, scholars and film fans never got the memo. From at least the mid-1930s up to the present day, Uchida has consistently been regarded in his native land as a very important, even seminal, figure in the history of the cinema of Japan.

I’ve compiled my own ranking of the most critically-acclaimed directors of the 1930s, based upon what is probably the only objective criterion: the ranking of Japanese movies in the “Best Ten” critics’ poll, held annually since 1926 by the venerable film magazine Kinema Junpo (“Cinema Times”), hereafter referred to as “KJ.” I have selected poll data from the years 1931 to 1939 inclusive, an era that I call the “Silver Age” of Japanese Cinema. (The KJ annual critics’ poll continues to the present day, as does the publication itself.)

I have given all filmmakers who directed films that appeared in the poll from 1931 to 1939 a point score based on their movies’ rankings in the poll. In other words, a film that ranked tenth in the critics’ poll in its particular year would earn 1 point, a film ranked ninth would earn 2 points, and so on, with the “Best One” of each year earning a full 10 points. Using this measurement, Uchida’s films earned 40 points over this nine-year period, based upon the five pictures of his that appeared in the poll, including the two chosen as the best film of their respective years, 1937 and 1939. (It should be noted that many other Uchida movies from this period, even first-rate ones like the surviving Police Officer, didn’t appear in the KJ poll at all.)

Thus Uchida, by this metric, ranks fifth in critical standing among all working directors during this time period. The four directors who scored higher than Uchida include the revered figures of Mizoguchi Kenji and Ozu Yasujirō (the latter was the overall “winner” with 50 points). Even such highly-respected artists as Yamanaka Sadao (who died in 1938), Naruse Mikio and Gosho Heinosuke didn’t achieve as high a score as Uchida. Therefore, if, at the very end of the 1930s, Japanese critics had been asked to vote on the ten living directors that they regarded as the most significant artistically, it’s safe to say that Uchida’s name would have appeared on every single list.

As for his postwar career, from his comeback in 1955 to his posthumously-released final film in 1971, he scored 24 points overall in the KJ polls, based upon the rankings of the six films of his that appeared in KJ’s Best Ten lists during this later period. This much lower score would seem at first glance to indicate a major falling off from his prewar reputation, but such an assumption would be very, very misleading. The starting point of this decade-and-a-half period, 1955, coincides with the absolute high point of the Golden Age of Japanese Cinema, arguably the greatest cinematic Golden Age any nation has ever enjoyed.

It should also be noted that, by the late 1950s, there were three great filmmaking generations active, all working at the top of their game: a) Uchida’s own generation, of which a significant number of prominent members, including Ozu, Naruse and Gosho, were still alive and working; b) the “war” generation, whose most legendary figure was Kurosawa Akira; and c) the first “postwar” generation, whose most famous figure was Oshima Nagisa, who was Uchida’s junior by over thirty years. All told, there were more than sixty significant active directors at the turn of the 1960s. (I’ve counted them.) When one considers this creative environment, in which quality movies (as judged by critics of the time) were released at a much higher rate than in the prewar era, and which was thus far more competitive, the fact that someone of Uchida’s advanced age (he was already 57-years-old when he began his comeback in 1955) and failing health could frequently manage to get his films cited in the yearly poll is remarkable.

There also exists a great deal of more subjective evidence pointing to Uchida’s high reputation in Japan, which, though anecdotal, is nonetheless persuasive. Below are three examples.

When Uchida returned to his native land in the mid-1950s after his long sojourn in China, his friends in the industry immediately set to work arranging his comeback. Shimizu Hiroshi was supposed to make a period comedy for Toei about a humble spear carrier, but he stepped aside to hand the project over to Uchida, and this project eventually became A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji, 1955). He and two other friends of Uchida’s, Ozu Yasujirō and Itō Daisuke, were credited as official “advisors to the production,” publicly lending their considerable prestige to the film. (It’s frequently alleged that Mizoguchi also helped out, including by Uchida’s son, Yusaku.) It seems wildly unlikely that these esteemed filmmakers would go to such lengths to help a down-on-his-luck filmmaker if they didn’t believe he was a peer, a figure artistically comparable to themselves.

Suzuki Toshio, the very successful producer at famed Studio Ghibli – responsible for many classic anime films by Miyazaki Hayao, Takahata Isao and others – has said in an interview that the very first film that impressed him as a child was Uchida’s Sword in the Moonlight trilogy (Daibosatsu Toge, 1957-1959). He recalled, “… of all the swordfight films that characterized Toei, this Daibosatsu Toge really stunned me.” (Suzuki was only nine years old when the trilogy’s first installment came out.) In the same interview, he claimed to have seen all of Uchida’s movies, and particularly praised the director’s Hero of the Red-Light District (Yōtō monogatari: hana no Yoshiwara hyakunin-giri, 1960) and A Fugitive from the Past (Kiga kaikyō, 1965). Suzuki added, “Miyazaki Hayao also singles out an Uchida work, Tasogare Sakaba [Twilight Saloon, 1955], as a film that shocked him. I loved this film, and Miya-san loved it too. Miya-san never watches films on video, but when he said he wanted to see Tasogare Sakaba once again, I brought in [to the studio] a video.”

Several original trailers for Uchida’s postwar works survive to prove that, in marketing his movies, Toei frequently exploited the director’s prestige as one of their films’ major selling points… sometimes the main selling point. In the coming attractions to The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi, 1962) – in a way not unlike the hype used for a Hollywood spectacular of the time – a title card boasts of “a star-studded cast.” But then it immediately adds “… by the great Uchida Tomu.” In the coming attractions of the fourth film of the Miyamoto Musashi series, the text proudly proclaims “a work by master director Uchida Tomu.” In the unsubtitled trailer for A Fugitive from the Past, a photo of the elderly Uchida’s smiling face is prominently displayed, implicitly putting him on a par with the star actors in the picture. Apparently, Suzuki Toshio was not the only moviegoer of the time who would eagerly pay to see a film simply because Uchida’s name was on it.

It often happens in film history that a director who more or less everyone agrees is a minor figure manages to create, over a long career, one great, classic film. Occasionally, such a moviemaker might make two such movies, or (very, very rarely) three classic works. But there’s no example of a minor director making half a dozen or more classic films, as Uchida did.2 In fact, the whole idea of separating artists into “major” and “minor” becomes utterly pointless if we concede that possibility. The evidence shows that among critics, his filmmaking peers, and audiences, recognition of Uchida’s excellence – indeed, uniqueness – was commonplace in Japan from the mid-1930s onward, and there’s no evidence that this high regard has in any way abated.

So to anybody who might ask me, “Why would you devote so much time and energy to create a website about such a totally obscure filmmaker?” I can only answer, “If you never see the films, you’ll never understand. But if you ever do see the films – or at least a few of the best ones – you’ll definitely stop asking that question.”

(Continued on Page 3)