Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Other titles: The Scaffold, They Are Buried Alive (alternate English titles)

| Production Company | Tōei (Tokyo) |

| Scenarists | Hashimoto Shinobu and Uchida Tomu |

| Source | Kikushima Ryūzō (book) and television film Dotanba (1956)1 |

| Cinematographer | Fujii Shizuka |

| Art Director | Mori Mikio |

| Music | Kosugi Taiichirō |

| Editing | Sōda Fumio |

| Performers | Katō Yoshi (Sunaga, the mine owner); Ebara Shinjirō (Yamaguchi, an apprentice miner); Nakamura Masako (Takahara Michiko, “Michi,” the winch operator); Okada Eiji (Shimano, a Korean miner); Shimura Takashi (Ban’no, a middle-aged trapped miner); Tōno Eijirō (Onishi, a foreman); Tonomura Shin (Kusaka, the Chief Miner); Ishimaru Katsuya (Noda, a trapped miner); Tachibana Yoshifumi (Yui, a trapped miner); Iwagami Ei (Ishigaki, a trapped miner); Takagi Jiro (Kondo); Kanda Takashi (Rikka); Namishima Susumu (Yokota, a former miner); Kazami Akiko (Kiku, wife of Noda); Takihana Hisako (Toshie, wife of Sunaga); Yamamoto Rinichi (Kawamura, miner and union leader); Iida Chōko (Ishigaki Kane, grandmother of Ishigaki); Saito Shiko (Inspector Yoshikawa); Suganuma Tadashi (Diver); Hanazawa Tokue (Takichi, Yokota’s enemy); Ueki Motoharu (Jirō, Michi’s younger brother); Kōdō Kokuten (Buddhist monk) |

| Status | Extant |

| Photography | Black and White |

| Format | 35mm |

| Ratio | 2.35 : 1 (ToeiScope) |

| English Subtitles | Yes |

| Original Release Date | November 24, 1957 |

| Length | 108 minutes |

| Awards and festival/retrospective screenings | Kinema Junpo “Best Ten” (at #7); MOMA Retrospective (2016) |

In a rural area of Japan near Nagoya, on a normal working day in a fierce, driving rain, the laborers of the Towa Mine work ceaselessly, bringing coal aboveground, preparing it for delivery and loading it onto trucks. Michiko, known as “Michi” or “Mi-chan,” operates the winch that moves the platform carrying men down into the mine and coal and men to the surface again.

In the main office of the mine, the elderly mine owner, Sunaga, interviews a young man, Yamaguchi, the son of a farmer, whom he immediately hires to begin working in the mine, starting the following day. He invites Yamaguchi to tour the mine that day to get a feel for the job from the other miners – with the Chief Miner, Kusaka, to show him around – and the young man accepts the offer. But Kusaka first informs Sunaga that a new frame that management had recently installed has displaced the old one, causing a serious water leak. Sunaga is angry because the cost of replacing the mine would be prohibitive. He tells the Chief Miner that “everyone should do his best,” and the latter is troubled by this inadequate response.

Down in the mine, the Chief Miner takes Yamaguchi through the various tunnels, ending up in the south tunnel. There Yamaguchi meets the elderly miner Ban’no, who knows the young man’s father well. In the northern tunnel, the Chief Miner observes that the constant water leak is much worse than before, and he appears very concerned.

Back aboveground, with the torrential and ceaseless rainfall, the water in the river is rising rapidly. The tower of the mine suddenly collapses and the frame gives way under the pressure of the leaking water. A deluge of water and a massive amount of debris fall into the mineshaft, flooding the mine and obstructing the shaft. The men in the mine, hearing the rushing water, are terrified and flee for their lives. The Chief Miner escapes through the northern tunnel, but five miners – Ban’no, Yui, Noda, Ishigaki and the young Yamaguchi – are forced to take refuge in the sixth coalface in the south tunnel, the only part of the mine above water level.

Sunaga orders his subordinate, Kondo, to contact the police and the miner’s union, while he runs to the adjacent, disused Ichikawa mine to see what he can do to help. The general alarm sounds and family members of the victims as well as rescuers rush to the scene. Kusaka informs a manager that the mine shaft to the Ichikawa mine is also flooded, and thus can’t be used to rescue the men.

At the disaster scene, the workers, with Michi’s help, lower a drainage pump into the mineshaft and begin pumping up water from the mine. At the sixth coalface, the five men, to their relief, notice that the water has stopped rising, and realize that their colleagues are working to rescue them.

At the mineshaft, Onishi the foreman tells the workers that if they can only get all the rocks out of the way, the water will be able to flow into the southern tunnel, lowering the water level and enabling them to get to the men. But Kawamura, the local union leader, complains that the water is so cold his workers can’t operate down there for more than five or ten minutes at a time. Onishi replies that five minutes at a time might be enough to do the job. Kawamura gruffly asks the managers to do it themselves if they think it’s so easy, which makes them angry. Shimano, a Korean miner, then volunteers to do this job and enlists his fellow Koreans to help him.

However, as soon as the rescuers pump water out of the mine, more water seeps in. Later, because of a power cut, the pump stops working entirely. Kawamura arrives at headquarters to tell the managers that if the power isn’t restored, the workers will have to start from scratch. He accuses the managers of not working hard enough and they are offended. When he leaves, one of the managers, sneering, says that the rescuers are only there to make money and get drunk, and his colleagues seem to agree.

At the sixth coalface, Yamaguchi can hardly breathe, but Ban’no comforts him, telling him that he was trapped underground twice in his life, the second time for 24 hours, but he survived. Meanwhile, Kawamura at headquarters, with the Koreans as witnesses, confronts the manager about his remark about the workers only wanting to “get drunk.”2 He reminds the bosses that the Koreans are there because no one else will do the job. The manager complains that the work is going too slow. Kawamura, incensed, responds that the workers are risking their lives, and if management isn’t satisfied, they should find someone else who can do it better. Kawamura orders the Koreans to go home and rest, and they suspend work on the rescue effort.

On the third day, a diver arrives and is lowered down into the mineshaft. When he comes back up, he tells Inspector Yoshikawa that he can’t work in such a narrow space because he fears that his oxygen tube will be accidentally cut, but at the urging of the distraught family members, he relents and agrees to try again. However, the diver fails and, after 80 hours, most of the crowd drifts away, having lost hope of seeing the men rescued.

Sunaga arrives at Noda’s house and is confronted by the angry family members. When Yui’s father asks what Sunaga intends to do about the situation, the weary owner answers that management will “do whatever it takes.” The men scoff at such a vague response. Ban’no’s brother-in-law reminds Sunaga that the accident was caused by a faulty frame, for which he is responsible. Noda’s wife, assuming her husband has already died, asks Sunaga to pay for the cost of cremating her husband’s remains so they can be shipped to his hometown. Sunaga insists that her husband and the other men are still alive and leaves on a bicycle. The brother-in-law calls Sunaga a miser. Kusaka, overhearing this conversation, is very upset.

The managers meet at two in the morning and Inspector Yoshikawa admits that though “everyone is at their limit,” there has been little progress. The doctor gives his opinion that, because of the rising carbon dioxide levels in the mine, they have only about ten hours, that is, until noon later that day, to save the five men. Kusaka, overhearing this, becomes even more distressed.

At the mineshaft, Onishi orders the workers to rest for a few hours and gather again in the morning. The men depart, leaving only Michi and Kusaka. The latter urges Michi to go home to sleep as well, but she decides to stay and sleep at the mine site, because otherwise she would feel as if she’s abandoning the trapped men.

Toshie in the countryside finds her husband Sunaga sitting, despondent, under a bridge. He tells her that he doesn’t know what to do. Toshie fears that her husband is contemplating suicide, but he denies this, saying that he can’t act “irresponsibly” at a time like this. He proposes instead that they sell their house and the mine to give the proceeds to the families – even though they’ll blame him anyway. However, if they did this, he says, he would have to go back to the mine as a common laborer, despite his advanced age. At that moment, Kondo arrives to inform the couple that Kusaka has just tried to hang himself at the mine. Sunaga goes to the hospital and speaks to the Chief Miner, who survived his suicide attempt, and Michi, who rescued him.

Sunaga arrives at the mine site and asks Kawamura if he would try to persuade the Koreans to come back to work. He agrees, inviting Sunaga to accompany him. The Koreans, with Kawamura and Sunaga present, decide, nearly unanimously, that, because the Japanese treat them with contempt – and since if they are injured or permanently crippled during the rescue operation, Workers Compensation wouldn’t cover their claims – they will refuse to participate in the rescue any longer. Sunaga rides away on his bicycle, totally defeated.

By the side of the road, Sunaga meets Yokota, a man who used to live in the town, but now works in a mountain village. He has just returned to help the trapped miners. At the mine site, Yokota is greeted warmly by the other miners who knew him long ago, and asks Michi to let him go down into the mine to try to deal with the problem, but he has no better luck than the other workers did.

Meanwhile, Shimano has a change of heart. He persuades his fellow Koreans to participate in the rescue effort anyway, because when he was a miner, he had always thought, “If something happens to me, my companions will help me.” Trucks full of the Koreans as well as other miners arrive at the site, delighting Sunaga.

At headquarters, Yokota tells the managers that their efforts so far have been wasted – but there’s another way. He reveals that, near the north tunnel of the Ichikawa mine, where military equipment was once stored during the war, there is now an empty space ever since the equipment had been removed, and this space was sealed by a concrete wall that he had helped build. If someone could dynamite this concrete barrier, water would then flow into the empty space, lowering the water level and allowing them all to proceed to the main mineshaft, where they could then dig away the debris to get to the southern tunnel and the trapped men. Inspector Yoshikawa agrees with this plan.

Yokota goes down into the flooded Ichikawa mine with Shimano and they cut a hole in the concrete wall in which they insert a stick of dynamite. When the men return safely to where the others are waiting, Onishi pushes a switch to explode the dynamite, smashing the concrete, and water flows into the space, lowering the water level in the north tunnel.

The men wade through the waist-deep water to the place where the rocks and debris had fallen down the mine during the cave-in. Yokota’s men start shoveling and clearing the dirt and rocks from the shaft so that another team of men going down the mineshaft can make contact with his team. At last, the workers below break through to the southern tunnel and begin to crawl through it. The rescuers reach the five men, but they are unconscious and apparently lifeless, and a doctor is lowered into the mine to examine them. Shortly afterwards, Inspector Yoshikawa announces over the loudspeaker the good news: the five men have been found alive!

A reporter tells his editor over the car phone that the men are being rescued after 98 hours underground — at the eleventh hour, just before they would have perished. An overjoyed Sunaga thanks everyone involved in the rescue. With Michi’s help, one by one the five men – Yui, Ishigaki, Noda, Yamaguchi and Ban’no – are brought up safely to the surface to be greeted by their relieved family members. Michi, exhausted, collapses in tears as Kawamura and Sunaga thank her. The crowd celebrates as the saved men are taken away.

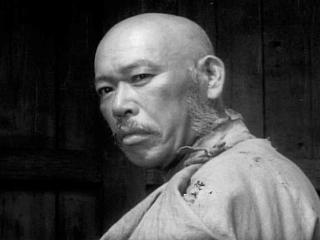

Shimura Takashi, in his long career, appeared in a great many roles for many directors. However, except for his performance as a scientist in the original Godzilla (Gojira, Honda Ishirō, 1954), he’s remembered in the West almost exclusively for his work for Kurosawa Akira, particularly his performances as the woodcutter in Rashomon (1950), as the dying bureaucrat Watanabe in Ikiru (1952) and as the master samurai Kambei in Seven Samurai (Shichinin no samurai, 1954, see photo). He had originally appeared in Kurosawa’s very first film, Sugata Sanshiro (1943), and gave memorable performances in the director’s Drunken Angel (Yoidore Tenshi, 1948), Stray Dog (Nora Inu, 1949), Scandal (Shubun, 1950), Record of a Living Being (Ikimono no kiroku, 1955) and, as a villain, in The Bad Sleep Well (Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru, 1960). He died in 1982 at the age of 78, after having made over 300 movies.

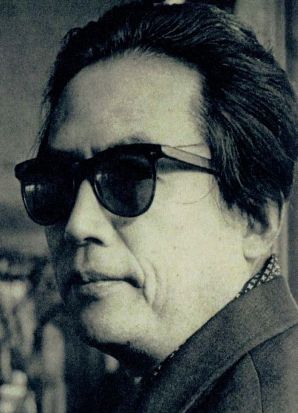

Okada Eiji had served in the Imperial Japanese Army and worked as a miner (among other jobs) before beginning a career as a film actor in the 1940s. He appeared in many films by distinguished Japanese directors, but ironically, his most famous role was in a film directed by a Frenchman: Alain Resnais’ classic Hiroshima, mon amour (1959), in which he played a man, known only as “lui” (i.e., “him”), who romances a mysterious Frenchwoman played by Emmanuelle Riva. He also acted opposite Marlon Brando in the Hollywood film The Ugly American (George Englund, 1963). His native productions included Mother (Okaasan, Naruse Mikio, 1952); Hiroshima (Hideo Sekigawa, 1953) – footage of which (without Okada) was included in the Resnais film cited above – Woman in the Dunes (Suna no Onna, Teshigahara Hiroshi, 1964) and Lady Snowblood (Shurayukihime, Fujita Toshiya, 1973). He also ran a theater company with his wife. He died in 1995, age 75.

Hashimoto Shinobu, like Shimura Takashi, was also strongly associated with the films of Kurosawa Akira, but his work as a screenwriter for that master was only one very important part of a long, varied and acclaimed career. While recovering from tuberculosis near the end of the war, Hashimoto decided to start writing screenplays. In the late 1940s, he contacted the already well-known Kurosawa to discuss a script he’d written, based on two stories by the early 20th Century writer Akutagawa Ryūnosuke. The director was impressed by the work of the novice writer and, after adding his own contribution, filmed the screenplay as the classic work, Rashomon – the movie that introduced Japanese Cinema to the West. For the next twenty years, Hashimoto co-authored seven more screenplays with Kurosawa, winning awards for Ikiru (1952) and The Hidden Fortress (Kakushi toride no san akunin, 1958). (The other five Kurosawa scripts he co-wrote were Seven Samurai (Shichinin no samurai, 1954); Record of a Living Being (Ikimono no kiroku, 1955); Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jō, 1957); The Bad Sleep Well (Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru, 1960) and Dodes’ka-den (Dodesukaden, 1970).) Late in life, Hashimoto authored a book, Compound Cinematics: Akira Kurosawa and I, about his work with the director. He also won awards for scripts written for many other directors, among them Naruse Mikio (Summer Clouds (Iwashigumo, 1958)); Kobayashi Masaki (Harakiri (Seppuku, 1962) and Samurai Rebellion (Jôi-uchi: Hairyô tsuma shimatsu, 1967)); Yamamoto Satsuo (The Great White Tower (Shiroi Kyotô, 1966)); and, especially, Nomura Yoshitarō (Stakeout (Harikomi, 1958), Castle of Sand (Suna no utsuwa, 1974) and Village of Eight Gravestones (Yatsuhaka-mura, 1977)). He also directed three films, including I Want to Be a Shellfish (Watashi wa kai ni naritai, 1959) and Lake of Illusions (Maboroshi no mizuumi, 1982). He also won an award for a script he co-wrote with Shindo Kaneto for director Imai Tadashi, Night Drum (Yoru no tsuzumi, 1958); both these writers eventually became centenarians, with Shindo and Hashimoto each dying at the age of 100, in 2012 and 2018, respectively.

(Continued on page 2)

[…] her work in Naruse Mikio’s 1950s films. During that time period, she also appeared in Uchida’s The Eleventh Hour (Dotanba, 1957). She died at the age of 78 in […]