Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Killing in Yoshiwara; Yoshiwara: The Pleasure Quarter; Tale of Strange Swords (alternate English titles); Meurtre à Yoshiwara (alternate French title); Cursed Sword Story: Flower of Yoshiwara, Hundreds Killed (approximate literal English title)1

| Production Company | Toei (Kyoto) |

| Scenarist | Yoda Yoshikata |

| Source | Kagotsurube Sato No Eizame (Kagotsurube: The Haunted Sword, 1888)2 by Kawatake Shinshichi II (uncredited) |

| Cinematographer | Yoshida Sadaji |

| Production Designer | Tamaki Jun’ichirō |

| Art Director | Suzuki Takatoshi |

| Music | Nakamura Toshio |

| Editor | Miyamoto Shintarô |

| Performers | Kataoka Chiezō (Sano Jirō, a silk manufacturer and merchant); Mizutani Yaeko [as Mizutani Yoshie] (Otsuru, an ex-convict, later the courtesan Tamazuru); Kimura Isao [as Kimura Ko] (Eiji, Otsuru’s pimp); Kataoka Eijirō (Jiroku, Jirō’s servant); Santō Akiko (Osaki, a worker in Jirō’s factory, Jiroku’s fiancée); Hara Kensaku (Echigoya, a merchant); Mishima Masao (Hyogoya, the brothel boss); Sawamura Sadako (Oken, the brothel madam); Chihara Shinobu (Yaegaki, a courtesan); Hanayagi Kogiku (Iwahashi, a courtesan); Chiaki Minoru (Jōsuke, a merchant); Takahashi Toyo (Okino, a brothel maid) |

| Status | Extant |

| Photography | Color |

| Format | 35 mm |

| Ratio | 2.35:1 (widescreen) |

| English Subtitles | Yes |

| Original Release Date | September 4, 1960 |

| Length | 109 minutes |

| Festival/Retrospective screenings | Tokyo FILMeX (2004); IFFR (International Film Festival of Rotterdam, 2005); Melbourne International Film Festival (2005); MOMA Retrospective (2016) |

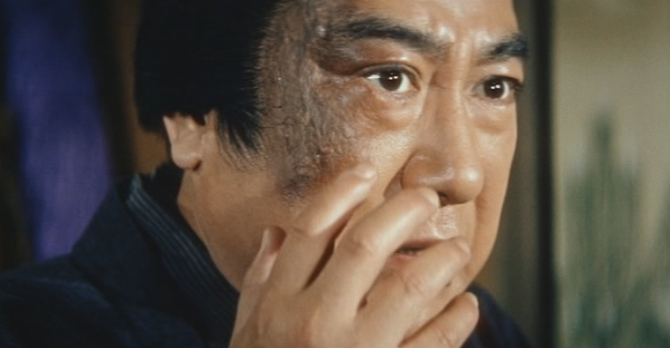

In a brief prologue, a prosperous but childless merchant couple in the feudal era of Japan discovers an abandoned infant on their doorstep. The wife points out to her husband that the baby has coincidentally appeared on the anniversary of the death of the couple’s only son, and asks him if they might raise the child, who’s clearly of samurai lineage, judging from a handwritten note and a short sword left behind with the infant. Examining the foundling more closely, the man notices that its right cheek is disfigured by a large and grotesque birthmark.

Years later, a middle-aged man, Sano Jirō, with the same birthmark – the foundling, now grown up – supervises his workforce in the prosperous silk factory he owns in rural Yashu (today known as Toshigi Prefecture). His servant, Jiroku, reminds Jirō that they soon must leave for the capital, Edo (the old name for what is now Tokyo). Jirō wishes to get married to honor his deceased foster parents and to produce an heir to inherit the business, and he has arranged through a client of his, a merchant named Echigoya, a matchmaking encounter with Echigoya’s homely, aging female relative. All the employees love their kindly boss, and one of them, the maidservant Oyasu, remarks that she hopes he finds a wife this time, as all previous attempts had failed.

In Edo, during a holiday celebration with fireworks, two boats on the river pass each other. In one of these are Jirō and his entourage; in the other are Echigoya, another merchant named Jōsuke, and the aging kinswoman of Echigoya. The woman gets a good look at Jirō and his birthmark and is visibly repulsed.

In Jirō’s rooms in Edo, he and Jiroku finish packing, getting ready to return immediately to Yashu. Echigoya arrives with his friends to tell Jirō, to his surprise and relief, that the woman had expressed a desire to be allowed “some months” to think over his marriage offer. Echigoya and the other merchants then invite him to accompany them to the licensed pleasure quarter, Yoshiwara. Jirō is initially hesitant, but out of politeness he accepts their invitation.

However, at Hyogoya’s brothel in Yoshiwara, to Echigoya’s embarrassment and Jirō’s shame, none of the courtesans want to serve the silk merchant, much less sleep with him, because his birthmark frightens and offends them. The brothel madam, Oken, reports this minor crisis to the brothel manager, Hyogoya. Having no other choice, Hyogoya orders one of the maids, Otsuru, to serve this “cursed” client, despite the fact that she’s merely a former street prostitute and convict, who’s received no training at all in the traditional arts of the courtesan. With a completely cynical and matter-of-fact attitude, Otsuru complies.

When Jirō and Otsuru are alone, Otsuru asks Jirō to pour sake for her, rather than the other way around. When Jirō asks if she’s offended by his “stain,” she laughs and tells him that there is no stain on his heart. She then kisses the cheek with the ugly birthmark, remarking that she “ate it all away.” It’s clear by his astonished reaction that Jirō has already fallen in love.

On the long walk back to Yashu, Jirō is cheerful, and Jiroku is glad that his master is happy. When they return to the factory, Jiroku reveals to his fiancée, the young factory worker Osaki, that Jirō had refused Echigoya’s kinswoman as a wife, and that this decision was made partly on the advice of Jiroku himself, who thought the prospective bride too old for his master. Osaki is displeased, as this means that she and Jiroku will need to delay their wedding again, since they can’t marry until the master has married, but the servant counsels patience.

At the brothel, Otsuru, as a lowly ex-convict, is scorned by the courtesans, her pariah status only confirmed by the fact that she now “sleeps with a monster,” Jirō. In a flashback, Otsuru recalls her arrest as an illegal prostitute – that is, one who works outside the licensed pleasure quarter – and her subsequent conviction, in which she was, ironically, assigned as punishment to work at the Hyogoya brothel in Yoshiwara. There she enviously witnessed the privileged treatment of the tayū, the highest-ranking courtesan.

Back in the present, Otsuru and the courtesans observe the funeral procession of a courtesan, Asazuma, from a rival house. No one from the woman’s family, they notice, had come to mourn or pray for her. The cruel courtesans predict that Otsuru will likewise end up in a common grave, but Otsuru says this will be their fate, while she herself will become tayū and be ransomed by a rich man.

Eiji, Otsuru’s former pimp, arrives at the brothel and demands to see Otsuru, which Hyogoya permits when he realizes that Eiji just wants to talk to her. Alone together, Otsuru bitterly blames Eiji for her arrest, and Eiji admits that if he had been with her instead of at a bar on the night the police came, she would never have been arrested. Otsuru allows Eiji, for whom she still has feelings, to make love to her.

Jirō returns to Edo on a business trip and stops by the brothel, where he negotiates with Oken the fee for Otsuru’s services. She sets the price for sleeping with Otsuru at five ryō, a very inflated price given her complete lack of skills, but the silk merchant, who expresses his desire to ultimately “buy” Otsuru, gives Oken fifty ryō to open an account for him, much to her astonishment. When Oken reveals this conversation to Hyogoya, he is pleased, as he judges Jirō a “bumpkin” whom they can easily exploit. Otsuru later complains to Jirō about her cruel life as a prostitute and, discovering that Jirō is unmarried, offers to become his wife – but only if he helps her become tayū first. He solemnly promises to make her happy by fulfilling her dearest wish.

Several weeks later, Oken compliments Jirō on his kindness to Otsuru, and informs him that his relationship with her has become the talk of the city. Echigoya then enters the room – along with Jiroku, who has journeyed from Yashu to Edo to deliver the sum of 200 ryō that his master had requested – and expresses concern to Jirō that his reputation, and by extension that of the merchant class as a whole, is suffering because of Jirō’s actions. To his surprise, Jirō, instead of apologizing, invites Echigoya to the brothel to meet Otsuru in person.

At Hyogoya’s brothel, the silk merchant and his guests, including Echigoya and Jiroku, are seated in a room when Otsuru enters and sits beside Jirō. She announces that she will become tayū, because he had promised to sponsor her. A courtesan sneeringly remarks to Echigoya that Otsuru doesn’t know the first thing about being a courtesan.

After Echigoya and Jiroku leave, Jirō seeks out Hyogoya and Oken. They falsely claim that he must bear the full expense of training Otsuru, as well as the cost of her accessories (including furniture) and that of the parade that will publicly proclaim her tayū status. They estimate the total cost at the whopping sum of a thousand ryō. The silk merchant is so drunk he doesn’t quite register what is happening.

Otsuru enters upon rigorous courtesan training, financed by Jirō. She learns to play the koto, is trained in the tea ceremony and is taught hand drumming. Jirō and Otsuru walk through the streets, proudly announcing the forthcoming parade in which Otsuru will be made tayū. All the courtesans laugh at the silk merchant, but he’s too happy and too proud of Otsuru to notice.

During a holiday celebration, Otsuru and Jirō are enjoying the street scene from an upper balcony of the brothel. Eiji arrives and demands from Hyogoya 10 ryō to pay for his journey to Osaka, promising that he will not make trouble for Jirō and Otsuru. Though he can easily afford the 10 ryō, Hyogoya indignantly refuses to be blackmailed. When Eiji informs him that he will get the money from Jirō directly, Hyogoya sends an assistant out into the street to follow the young pimp.

Eiji breaks in through a window of the brothel and finds Jirō and Otsuru together. The quick-witted Otsuru, calling Eiji her “brother,” demands that he leave. Without exposing her lie, Eiji demands 10 ryō from Jirō, promising to go away so they can celebrate his “sister’s” promotion in peace. At that moment, Hyogoya’s assistant and several other thugs approach the room. The pimp tells the silk merchant to leave the 10 ryō with Otsuru so he can pick up the money later, and escapes through the window. When the thugs enter the room and realize that the pimp has already gone, they excuse themselves and go down into the street to chase him.

Later, in a marshy area just outside the city, in sight of the lights of Yoshiwara, Eiji runs away from the men, but they surround him. He pulls a knife, but they stab him repeatedly, killing him. They cover his body and leave it to rot in the marshland.

Meanwhile, at the brothel, Otsuru explains to the silk merchant that her “brother” is a yakuza and that she never wants to see him again. Despite this, Jirō asks if a 10 ryō payment would be enough, and Otsuru happily accepts it. Hyogoya arrives to apologize for Eiji’s interruption. He then changes the subject to the price of Otsuru’s promotion… which has now risen from 1000 to 1300 ryō. The silk merchant is stunned, but doesn’t object to the increased price. He then is notified by a servant that an employee from his hotel has arrived with a message for him. Going downstairs, Jirō is handed a scroll with the news that severe hailstorms have been devastating Yashu.

At the factory in Yashu, Jirō’s subcontractors report to him that the hailstorms were so bad that the bushes were stripped of their leaves, and as the silkworms have no leaves to eat, they are dying. They urge him to buy the bushes spared from the hail and collect them, so that the silkworms will eat the leaves and survive. Jirō gives Jiroku 200 ryō for this purpose, as well as an extra 300 ryō to purchase silk thread in bulk for the subcontractors. Jiroku is distressed by his master’s excessive generosity.

To put additional pressure on Jirō, Hyogoya persuades Otsuru to write a letter to the silk merchant claiming that a (fictitious) rich sake merchant wants to buy out her contract. When Oken warns Hyogoya that perhaps they’re going too far, he points out that, due to Jirō’s recent business reversals, he may soon have no money left, and that therefore they should “bleed the pig before it dies.” To deliver Otsuru’s letter, he sends to Yashu a messenger, who reminds Jirō that he still owes 1300 ryō for Otsuru’s expenses. Since the silk merchant is clearly unable to pay this sum, the messenger requests, as a kind of down payment, “only” 500 ryō, so that Otsuru will not have to resume taking other clients. Very reluctantly, Jirō pays the man this amount.

The silk merchant, in a room containing a shrine to his foster parents, picks up the short sword that had been left when he was abandoned as an infant. At that moment, Jiroku arrives with more bad news: the subcontractors are claiming that all the thread that Jirō had purchased for them with his 300 ryō is unusable. Jiroku is extremely skeptical of this claim, but Jirō insists that if they say so, it must be true. The servant warns the silk merchant that their own stocks are empty and so they’re in no position to help the subcontractors any longer. However, Jirō points out that he still owns the sword, which Jiroku should be able to sell in Edo for “at least” 1000 ryō, and adds that he intends to borrow another 1000 ryō from Echigoya to help the subcontractors.

In Edo, Echigoya agrees, with his associates, to give Jirō a bill of exchange for the 1000 ryō he’s requesting. They have just one stipulation: that he completely cut all ties to Yoshiwara immediately, as the merchants, to preserve their reputations, don’t wish to lend their money to a man linked in public opinion with the pleasure quarter. Jirō readily agrees to these terms, and the merchant gives him the bill of exchange.

In a café near Yoshiwara, Jirō explains to Jiroku that he plans to persuade Hyogoya (presumably by writing to him) to put off from March until August the parade in which Otsuru would be promoted to tayū. If the brothel boss agrees, Jirō explains, his financial situation by that point should have stabilized to the point that he can then pay Otsuru’s expenses and marry her.

Going out into the street wearing a sedge hat over his eyes so as not to be noticed, Jirō, as he passes the brothel, is nonetheless recognized by one of the courtesans, Iwahashi. She informs him that Otsuru’s contest, in which a jury will decide whether she’s to be promoted to tayū, is in progress. Despite his promise to Echigoya, Jirō allows Iwahashi to lead him into the brothel.

Jirō witnesses Otsuru performing a dance. The courtesan who’s been training her declares that she’s not yet ready to be promoted. Disregarding this, the jury (which has been bribed by Hyogoya) votes unanimously to approve her. Otsuru is triumphant and Hyogoya congratulates Jirō, who is nonetheless depressed.

Otsuru proudly shows Jirō her luxurious new quarters, which his fortune has provided for her. Hyogoya and Oken enter and Jirō asks them to postpone the parade until August. Both the boss and the madam feign outrage at this suggestion. The only way they would postpone the event, they tell him, is if he were to pay them additional fees to compensate for Otsuru’s “lost” income over the months of delay. Since she is now a tayū, they explain, she can now charge clients at least five ryō per night. Since there are 180 days remaining until August, Jirō would need to pay the brothel keepers 900 ryō over and above the 800 ryō he still owes them, totaling 1700 ryō – in addition to the fortune he’s already paid them. Jirō angrily denounces their insatiable greed.

Unfazed, Oken demands that Jirō pay the 800 ryō upfront now, and asks if he has this money on him. Although he has the 1000 ryō bill of exchange on his person, he refuses to give this up, and Hyogoya informs him that they will give Otsuru to the (fictitious) sake merchant instead. Oken, no longer needing to flatter Jirō, calls him an “idiotic monster,” at which Jirō recoils in horror, touching the “stain” on his face.

Jirō turns to Otsuru to ask if she, defying the brothel managers, will agree to a postponement, but she refuses. She then reveals that she was motivated all along not by love for him, but to make herself tayū to revenge herself upon the courtesans who despised her, and then to marry a rich man – no matter who that man might be. He accuses her of lying to him, but she insists that she did not lie: she would gladly have married Jirō if he still had the money to pay her ransom.

When he confronts her with her letter about the sake merchant, she reveals that it was dictated by Hyogoya. She sums up his situation with the words “no more money, no more love.” When the boss then demands that Jirō leave, he furiously declares that he will find the money they’re demanding and storms out of the brothel.

In the street, he finds Jiroku and asks how much money he’d gotten for the short sword. The servant sorrowfully admits that he couldn’t sell the weapon. Because it was forged at Kagotsurube, it’s a “cursed” sword and no one will buy it from him.

Echigoya and the other merchants appear in the street, having followed Jiroku to Yoshiwara. Echigoya scolds the silk merchant for breaking his word and returning to the pleasure quarter against their wishes, and he accuses Jirō of having spent the 1000 ryō bill of exchange. The silk merchant produces the document to prove he had not spent it, but Echigoya is unimpressed. Being a merchant is a matter of trust, he declares. Since Jirō had broken that trust by going to the pleasure quarter, Echigoya demands that he return the bill of exchange – which he does.

Jirō and Jiroku arrive home in Yashu in a despairing mood. They find Osaki still working at her loom. She asks Jiroku what happened in Edo, but he doesn’t answer. Jiroku returns the unsold sword to his boss, but instead of putting it back in its place in the shrine room, Jirō takes it away with him into a small room off to the side, and closes the door. Jirō removes the sword from its sheath, and examines it, apparently about to kill himself. Suddenly, he hears an infant’s cry and looks around, startled. The gigantic image of himself as an infant, with the large birthmark on its right cheek, appears.

The following morning, Jiroku, Osaki and the maidservant Oyasu gather outside the room in which Jirō had locked himself in, all fearing the worst. However, the silk merchant opens the door and appears alive and well, carrying a portable tea tray and instructing Oyasu to prepare sake. He informs Jiroku that he intends to settle in Kyoto and become a wholesaler, restarting his career from scratch, and that he will turn his house over to him. Jirō plans to give the cursed sword to a local temple, travel to Edo to say goodbye to Echigoya and then leave immediately for Kyoto. Jiroku and Osaki weep for their beloved, but now completely ruined, boss.

Oyasu returns with the tea tray with the sake and Jirō announces that he will marry them. Instead of being elated, however, they are heartbroken. He has Oyasu pour sake for Jiroku and Osaki, and sings them a wedding song about the happiness of a married home, but there’s no happiness in Jirō’s (now Jiroku’s) home.

In Edo, the day of the promotion of Otsuru (now Tamazuru) finally arrives as scheduled. She parades through the street, followed by Hyogoya and Oken, as many onlookers watch. As she walks by in her elaborate costume, bystanders comment upon how extraordinary it is that an ex-convict has become the “queen” of courtesans.

Nearby, Jirō, his face obscured by a sedge hat, witnesses this once longed-for event with fascination and horror. Jōsuke the merchant, whose conversation Jirō overhears, is astonished to discover that the silk merchant covered the entire cost of Otsuru’s promotion to tayū, and that Hyogoya, whose responsibility this should have been, paid nothing. Jōsuke calls Hyogoya “the worst of the scoundrels,” but another merchant calls Jirō “the king of the vacuous”… and a “monster” as well.

At these words, Jirō pushes his way through the crowd into the middle of the street, despite the efforts of the guards to stop him. He removes his hat and Otsuru, Hyogoya and Oken recognize him with horror. Hyogoya and Oken angrily ask him if he is crazy; he responds by unsheathing his sword and attacking them, killing first Oken and then Hyogoya.

People all over Yoshiwara panic and run for their lives. Jirō chases Otsuru who, because of the koma-geta (high platform shoes) she is wearing for the occasion, can’t run but can only walk slowly away from him. The alarm bell is sounded, and, after several dozen police enter, guards close the gates to the pleasure quarter, allowing no one to enter or leave.

Brothel guards try to protect Otsuru from Jirō’s attack, but with almost superhuman strength, he casually brushes them all aside, killing many of them. Otsuru, who has fallen to the ground, desperately tries to crawl away. She finally reaches the locked gate and tries to open it, but there’s no escape.

Jirō fends off all his attackers and finally stabs her in the back, leaving her mortally wounded. He dementedly cries out to his tormentors to leave him and his “wife” alone. He calls on all the “scoundrels” of Yoshiwara to “come out,” declaring that he will kill them all, as cherry blossoms fall all around him.

Mizutani Yaeko [Mizutani Yoshie] – Daughter of a successful actress (who was also known as Mizutani Yaeko), Mizutani started her career right after the war as a child performer. Beginning in the mid-1950s, she began to bill herself as Mizutani Yoshie. In addition to this movie, she appeared in many other period films, including episodes of two popular, long-running franchises: the Zatōichi series (The Tale of Zatōichi Continues (Zoku Zatōichi monogatari), 1962) and the Sleepy Eyes of Death series (Sleepy Eyes of Death: The Mask of the Princess (Nemuri Kyōshirō: Tajōken), 1966). Although she left movie acting at the end of the 1960s, she has returned to films in the 21st Century.

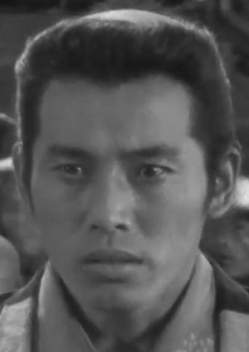

Kimura Isao [Kimura Ko] – Kimura was a popular star who, like Chiaki Minoru (who also appears in this film), was strongly associated with the work of Kurosawa Akira. His breakthrough role came in that director’s classic 1949 detective film, Stray Dog (Nora Inu). Though 26 at the time that film was released, he looked considerably younger, and throughout much of his career he portrayed characters who appeared younger than his real age. His classic role was as the adolescent apprentice samurai, Katsushiro, in Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (Shichinin no Samurai, 1954) – though he was already about 30 years old at the time – and he appeared in less prominent roles in the same director’s Ikiru (1952), Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jō, 1957) and High and Low (Tengoku and Jigoku, 1963). He also appeared in films by Naruse Mikio, Imai Tadashi, Shinoda Masahiro and many other filmmakers. For Uchida, Kimura would later give a memorable performance as Musashi’s hapless friend Matahachi in the five-part Miyamoto Musashi series (1961-1965). He also headed his own theater troupe, which eventually went bankrupt. He died in 1981 at age 58.

Mishima Masao – Beginning his film career in the mid-1930’s, Mishima, with his Buddha-like appearance, became a familiar character actor in the postwar era. He was effectively cast in both benign roles, like the affable family friend Onodera in Ozu’s 1949 classic Late Spring (Banshun), and not-so-benign ones, such as the cowardly labor camp commander in Kobayashi Masaki’s The Human Condition (Ningen no Joken, 1959), or the corrupt clan member in the same director’s 1962 masterpiece Seppuku (Harakiri). He also served as a voice actor in animated works, including Takahata Isao’s groundbreaking 1968 directorial debut, Horus: Prince of the Sun (Taiyō no ōji: Horusu no daibōken). He died in 1973 after having performed in over 160 films.

Sawamura Sadako – Born in Tokyo’s then-impoverished Asakusa district, Sawamura became one of the most prolific and popular of all Japanese character actors. Hers was an exceptional acting family: her brothers were Sawamura Kunitarō, who appeared in Yamanaka Sadao’s classic 1935 comedy Sazen Tange and the Pot Worth a Million Ryo (Tange Sazen yowa: Hyakuman ryō no tsubo), and the beloved character actor Katō Daisuke (see A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji and Twilight Saloon). Her nephews were Nagato Hiroyuki, who starred in Imamura’s Pigs and Battleships (Buta to gunkan, 1961), and Tsugawa Masahiko, who appeared in Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff (Sanshō Dayū, 1954) and Nakahira Ko’s Crazed Fruit (Kurutta kajitsu, 1956). She performed in numerous films by such well-known masters as Mizoguchi, Ozu and Naruse, as well as in works by Imai Tadashi, Kinoshita Keisuke, Nomura Yoshitarō and many other directors. Uchida had previously cast her in The Great Bodhisattva Pass trilogy, and she would later appear, again playing a madam, in A Fugitive from the Past. She also enjoyed a prominent career in theater and television. An English translation of her popular memoir depicting the struggles of her youth, My Asakusa, was published posthumously in 2000. She died in 1996, age 87.

Santō Akiko – A grand-niece of a politician who served in the Japanese House of Representatives, Santō became a child star in 1957, and was only 18 when she appeared in this film. After performing in about two dozen movies, mostly in supporting roles, she retired from acting in the early 1970s, and a few years later she decided to go into politics herself. In 1974, she was elected to the House of Counsillors, the upper house of the Japanese Diet, as the youngest member ever, at age 32. She has served there, on and off, for over 45 years. In 2019 she became President of the House of Counsillors (a post she still holds in 2022), making her the (approximate) Japanese counterpart of Mitch McConnell in America. Thus, she has enjoyed the most successful post-acting career of any performer in any of Uchida’s movies.

(Continued on page 2)