Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from page 1)

“Even finer [than Itō Daisuke’s The Conspirator (Hangyakuji, 1961)] is Killing in Yoshiwara (1960), directed by Tomu Uchida (1897 [sic] – 1970) who, on this [film’s] evidence alone, was the equal of Mizoguchi and Kinugasa… one of the most splendid of Japanese historical films… Uchida handles the battles [sic] brilliantly…”

‒ From David Shipman’s The Story of Cinema1

“Whoever loses, wins…”

‒ Dialogue by a performing comedian in the film

The events of this movie – however strange or even improbable they may seem – are based, though very loosely, on an actual incident that occurred in early 18th Century Tokyo (then known as Edo). During that era, known as the Kyōhō period (1716-1736), a rich farmer named Sano Jirōzaemon (Sano Jirō in the film), whose face was alleged to be disfigured by pockmarks as a result of smallpox, attacked a famous, high-ranking courtesan he’d fallen in love with named Yatsuhashi, killing her and dozens, perhaps hundreds, of others before being captured.2 An entire kabuki sub-genre of plays, called sano-yatsuhashimono (“stories of Sano and Yatsuhashi”), deals with the doomed real-life relationship of Sano Jirōzaemon and Yatsuhashi.3

The most famous version of this story is the kabuki play Kagotsurube: The Haunted Sword (Kagotsurube Sato No Eizame) by Kawatake Shinshichi II, which premiered in 1888, more than a century-and-a-half after the real-life event.4 The film is very loosely based upon this work: in the movie, a totally different female character – the false courtesan Otsuru, a.k.a. “Tamazuru,” who’s actually a mere street prostitute and ex-convict – has been substituted for the play’s famous heroine. This may explain why, in the opening credits, no source is given for the screenplay.

The sword in the play is “haunted” because it was manufactured at Kagotsurube by a famous swordsmith, Muramasa, who lived in the 16th Century. The katana that Muramasa crafted were famous for their high quality and were at first much favored by members of the ruling Tokugawa dynasty. But somehow the swords later became associated with the movement against the Tokugawa shogunate, and so by the early 18th Century they were regarded as “cursed” swords (yōtō), which meant that no one would buy them. So it’s not just a hokey invention of the filmmakers when Jiroku in the film tries to sell Jirō’s short sword, his only possession of value – which, unbeknownst to him, is a Muramasa-forged weapon – but is unable to do so because of the curse upon it.

Though there’s no direct proof of this, it’s possible to see the film as strongly influenced by Shakespeare’s strange play Timon of Athens (written ca. 1606). In that work, as in Uchida’s movie, a kindly rich man is driven to furious rage by the greed and ingratitude of people he had trusted. But if the screenwriter, the great Yoda Yoshikata, or Uchida did indeed employ this drama as an unacknowledged source, the differences between the two works are as telling as their similarities.

Timon, after being betrayed by his parasitical “friends,” rejects mankind in general and Athens in particular. Jirō only turns against the culture of Yoshiwara, not the city of Edo as a whole, much less the human race. Timon’s reaction to his betrayal is to become a hermit and live in a cave; Jirō’s demented response is to attack and kill his persecutors, including Otsuru. In the play, Timon in his cave initially regards his steward, Flavius, with the same contempt as all other men, until the servant’s tears convince Timon of his sincere love for his former master. Jirō, on the other hand, never rejects his servant Jiroku or any of his employees, whose love for him he has never been given any reason to doubt. Finally, Jirō possesses an awareness of self and (until he goes mad) a dignity that Timon lacks, as the silk merchant seems conscious of the fact that it was his own weaknesses that led to his destruction.

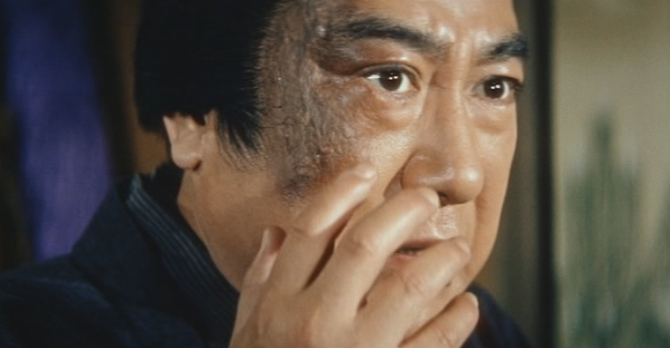

It has occurred to me that the decision of the filmmakers to restrict Jiro’s birthmark to only one cheek – a detail that doesn’t correspond to Kawatake’s play, in which the hero’s entire face is pockmarked – may have been inspired by Uchida’s, or Yoda’s, reading of Marx. (We know Uchida studied Marx before the war, and he certainly became re-acquainted with his works during his sojourn in Communist China, where he was forced to attend political education study groups; Yoda was also associated with the Left in the prewar period.) At the end of Chapter 31 of the first volume of Capital, Marx writes, “If money, according to [Marie] Augier [author of the 1842 work, Du Crédit Public], ‘comes into the world with a congenital blood-stain on one cheek,’ capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”5 6

Thus, from a lurid story about a foolish, disfigured and dangerous bumpkin, a haughty and fickle courtesan and a “cursed” sword, Uchida and his screenwriter, Yoda Yoshikata,7 fashioned a cinematic masterpiece.

Although the 1965 film, A Fugitive From the Past (Kiga Kaikyo), is more often cited as Uchida’s finest film, the screenplay to this earlier film is definitely the best ever written for any surviving work by Uchida I’ve seen, including Suzuki Naoyuki’s script for Fugitive, which, in my opinion, gets bogged down a bit too much in tedious police procedure (though I’m sure detective-movie fans most enjoy precisely this element in the film). In Hero, the beautifully-structured narrative moves relentlessly forward, yet never feels rushed. It is like a great river: a powerful, irresistible, yet somehow unhurried current.8

This leads to a tantalizing question, which could also be asked of many other works by this director: how much of this script was the credited screenwriter’s, and how much of it was composed by Uchida himself? Like so many Japanese directors, Uchida was also a scriptwriter. The Internet Movie Database lists a total of ten writing credits for him, including the last four installments of the Musashi series of the early-to-mid-1960s (the whole five parts of which I would count as one work). However, this underestimates somewhat his total number of credited contributions, since my most reliable Uchida filmography includes several early silent movies for which he was credited with writing the story or the screenplay or both, credits not acknowledged by IMDb. But the fact remains that for virtually all his most important surviving films, Uchida claimed no screenplay credit at all, a fact which would, in some quarters, disqualify him as a true auteur.9

Japanese film scholar Joan Mellen, in an interview with Uchida’s younger contemporary, director Kobayashi Masaki, asked him if he wrote the screenplays for his films. He replied, “I always try to bring in one professional scenario writer. I usually let him work first. After he has said he has put in everything he thinks appropriate, then I start to write the scenario myself.”10 This is very interesting, because on IMDb, for those films he himself directed, Kobayashi is credited as screenwriter or co-screenwriter on only four: the early work Three Loves (Mittsu no ai, 1954); the three parts of The Human Condition, considered collectively as one work (Ningen no jōken, 1959-1961); the documentary Tokyo Trial (Tōkyō saiban,1983); and his final film, Family Without a Dinner Table (Shokutaku no nai ie, 1985). Obviously, then, Kobayashi is implying that he worked on the scripts for many more films than the ones on which he was officially credited. In a similar way, Uchida may well have extensively revised the scenarios he was given by his designated screenwriters without taking credit for his contribution.

To illustrate this point, it should be noted that this film and its immediate predecessor, Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (Naniwa koi no monogatari, 1959), are the most similar of any two surviving films that this supremely versatile director ever made. (My personal nickname for them is “the twins.”) The two works are both adapted from source material taken from the repertoire of Japan’s traditional theater; they share many of the same themes, including, of course, the theme of prostitution; they employ a very similar visual style and rhythm; and they both use color in much the same way.

Yet the scripts for these two films are credited to two completely different screenwriters – Narusawa Masashige wrote the earlier film – and there were also two different cinematographers involved: Tsudoi Makoto shot the earlier film; Yoshida Sadaji lensed this one. The creative intelligence that made, of these paired works, two related variations of the same artistic vision is clearly Uchida’s. But a definitive answer regarding the extent of the director’s involvement in the writing phase of this film would require, of course, a detailed examination of the actual shooting script… a topic for future scholarship.

Whoever may have been responsible for the script for Hero of the Red-Light District, it is quite different from the more famous ones that Yoda co-wrote for Mizoguchi, such as The Life of Oharu, Ugetsu monogatari and Sansho the Bailiff. Those earlier movies, despite their harsh subject matter, are much gentler. In other words, the characters suffer, but the goal isn’t to make the audience suffer. But Uchida’s film is, I would claim, one of the first to belong to a contemporaneous type of Japanese film called the zankoku (“cruel”) film. Zankoku movies – some of them even include the Japanese word in their titles11 – eschew sentiment to give an allegedly more realistic and much more brutal vision of Japan, either in its 20th Century reality or in its fabled historical past.

What distinguishes a zankoku film is its harsh tone, not merely the frequency or the explicitness of its violence. Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, for example, which was released in 1954, is not a zankoku film, despite its plentiful and (for its time) realistic swordplay. But Yojimbo, a much more cynical and much bloodier – though tame by today’s standards – black comedy by the same director, released only seven years later, is definitely a zankoku film.

Such films were designed to appeal to a young, cynical and (largely) male generation of Japanese who had few if any memories of the recent war and fewer illusions about the nation their elders had bequeathed to them. These young viewers were having none of the uplifting stories that sustained their parents during the tough early postwar years. They’d grown up in a world of corrupt politics and cutthroat business ethics, and they demanded to see these dark realities reflected on the screen. (One of the biggest hits from this same year, 1960, was Kurosawa’s The Bad Sleep Well (Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru), about high-level executives who resort to murder to hush up a corporate scandal.)

The upside of zankoku films is that they made possible a stronger and more direct critique of political and social realities than the Japanese movies of any era since the keikō eiga (leftist tendency) films of the late 1920s and early 1930s. The downside of such films is a tendency to indulge in sex and violence for their own sensationalistic sake.

The cruel nature of Hero of the Red-Light District is enhanced, ironically, by its predictability. It’s obvious from the beginning of the narrative that the relationship between the silk merchant and the courtesan will end badly. Each step in the hero’s path towards self-destruction thus becomes painful for the audience to watch, like witnessing, from a distance, a train wreck in slow motion.

It should be noted that the character of the prostitute heroine of Uchida’s previous film, Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka – the compassionate, romantic and altogether lovable Umegawa (played by Arima Ineko) – is as opposite as can be imagined to the anti-heroine of this film, the vulgar, grasping, unfeeling Otsuru. Both women’s relationships end in disaster, but the sad story of Umegawa and the foolish clerk Chubei contains a redemptive element in the undying love between the two young people. No such redemption can be claimed for the later film; indeed, one of the two “lovers,” Otsuru, dies at the hands of the other.

Uchida is sometimes referred to as a nihilist, and this film more than any other is cited to support this view. But it should be noted that there always remains for Jirō the possibility of escaping his fate. Thus his bleak story retains the one factor crucial to true tragedy: choice.

Near the beginning of the narrative, after Echigoya’s aging but respectable female relative – for whom that merchant had arranged a matchmaking meeting with Jirō in Edo – gets a good look at the silk merchant and his “hideous” birthmark, she surprisingly doesn’t reject him out of hand. She merely asks for a few more months to think the matter over. The request for time is almost certainly a mere face-saving ploy for the woman, who is doubtless ashamed at being so desperate to marry that she’d even consider such a “monster” as a potential husband.

In any case, there remains little doubt that the woman would have ultimately accepted him, though unwillingly, if he had accepted her. It’s the combination of Jirō’s terrible luck in meeting Otsuru at precisely this moment, and his own almost infantile need to trust anyone who appears to accept him as a human being, stain and all, that doom him at the very moment when a safe escape from his celibate condition finally presents itself.

Jirō’s tragic fate is best illustrated in the scene that remains my personal favorite of all Uchida’s movies. In fact, if I were asked to choose only one scene to prove Uchida’s greatness as a filmmaker, it would be this one.

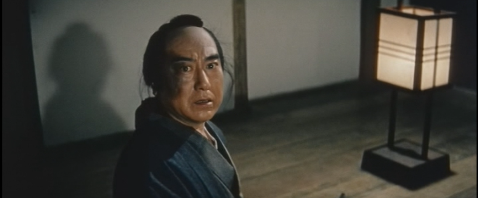

The silk merchant, now utterly ruined, unexpectedly retires to a small room of his house with the cursed short sword. His employees (and the audience) anticipate the worst, especially as he is an unacknowledged scion of a samurai family, for whom suicide would be a perfectly appropriate response to his very public disgrace. However, Uchida uses none of the usual filmmaking ploys to ratchet up tension: there is no music on the soundtrack, no attempt by the filmmaker to heighten the moment through editing or other means. Yet the suspense is enormous. Jirō unsheathes his sword, and silently examines it, preparing to strike himself.

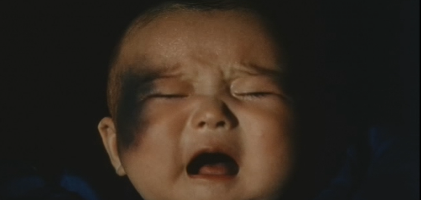

Out of nowhere, though, he, and we, hear a baby’s cry. He looks around, startled. Then, unexpectedly, Jirō – or rather the actor, Kataoka Chiezō – looks up and straight into the camera, breaking the “fourth wall.” Suddenly, there’s an enormous closeup of Jirō as a baby, crying, with the dreadful birthmark on his face. It’s as if the ghost of Jirō’s own infancy had appeared in order to affirm his lifelong curse… and to distract him from the too-easy solution of suicide. This may be the most visually compelling cinematic image I’ve ever seen of the destructive impact of the past upon the present.

Hero of the Red-Light District, despite its brutal tone, is a true tragedy, not merely a cynical, merciless melodrama.

In this film, as in Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka, the director establishes explicit parallels between the world of the merchant class (Uchida’s own class) and that of the pleasure quarter, emphasizing the common motive force of avarice linking the two. For example, both Jirō and Hyogoya, the brothel boss, remind their employees (factory workers and prostitutes, respectively) to turn the fires off in their workplaces before closing up shop for the night.

After Jirō’s first visit to Yoshiwara, Jiroku, his servant, brings back to Yashu ukiyō-e prints of the famous courtesans, and the female workers in Jiro’s factory gather round to admire and collect these art works. But at the same time that those esteemed printmakers are glorifying the courtesans and their beauty, society as a whole, and even their own families, paradoxically shun them as sexual outlaws, despite the fact that their trade, like that of the merchants who exploit them, is perfectly legal, at least within the bounds of the red-light district. For however educated, refined and multi-talented the courtesans may be, they’re all, in the end, for this patriarchal society, just whores, despised as disposable merchandise. Uchida’s implied comment upon 20th Century popular culture – in which exploited film or pop music stars are simultaneously worshiped and reviled, and their private lives salaciously exposed – is clear.

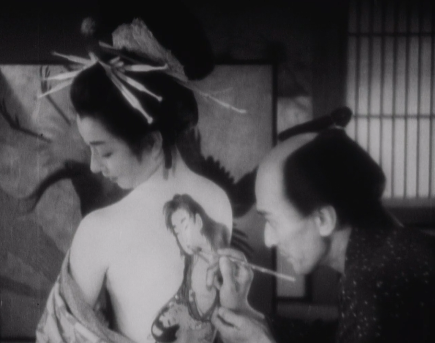

Intentionally or not, this scene, and indeed the movie as a whole, seems to serve as a critique of Mizoguchi’s 1946 film Utamaro and His Five Women (Utamaro o meguru gonin no onna: literally, “Five Women Around Utamaro”), in which the erotic demimonde of “fallen” women is depicted primarily as a source of inspiration for the genius male hero. (In a famous image from Mizoguchi’s film, the ukiyō-e painter Utamaro is shown using the naked back of a woman as, literally, a canvas for a new art work, blending artistic objectification with sexual objectification.) And it’s not impossible that Uchida is also consciously critiquing himself, because he, like Mizoguchi, is exploiting the sufferings of women of a long-past era for cinematic purposes.

For Mizoguchi, the alleged “transcendence” of Art – yet another exclusively male prerogative – was ultimately sufficient to vindicate the extreme suffering of women. But Uchida seems to have had a problem with this self-serving (from the artists’ point-of-view) notion. The last sound we hear in Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka originates not from the concluding performance of Chikamatsu’s Bunraku play, in which the agony of the doomed lovers is refined and purified by his dramatic genius, but the anguished – “unfiltered,” as if were – cries of the real Umegawa, which the compassionate playwright apparently can’t get out of his head.

The link between the merchant class and what might be called “the procuring class” can be best explored by comparing the most typical representatives of each of these two groups in the world of the film: the respectable Edo merchant Echigoya and the brothel boss Hyogoya. Both are obsessed with appearances, and both are quick to take umbrage at perceived challenges to their respective domains.

When the foolish and chronically broke pimp Eiji – who’s obviously not a “businessman” like Hyogoya – demands as blackmail 10 ryō from the latter, the brothel keeper is genuinely outraged, and is willing to go to great lengths, even murder, rather than pay this lowlife what for him would be a very modest sum. Significantly, Eiji’s killing, which takes place almost exactly halfway through the film’s running time, not only foreshadows the film’s even more violent conclusion, but reveals the true extent of Hyogoya’s viciousness. In a brilliant detail, as Eiji is killed, Uchida shows us in the distance the dazzling lights of Yoshiwara: the town is much too busy with its pleasure-seeking and money making to heed the fate of a man as insignificant as Eiji.

Hyogoya and his partner in crime, the madam Oken – beautifully played by Sawamura Sadako – are the most hateful characters in any Uchida film I’ve ever seen. Compared to them, the serial killer Inukai in A Fugitive from the Past is an angel. But they are also idiots who think they’re geniuses, stupidly and smugly assuming that Jirō will go away and leave them alone after they’ve destroyed him.

Echigoya is also vicious, but in a much more subtle way. When he invites Jirō to Yoshiwara during his first visit, he does so in the same spirit in which a modern host residing in a great city might treat a guest to a tour of one of that city’s most interesting and colorful landmarks. It’s clear that the Edo merchant is very familiar with the pleasure quarter, and it’s not unlikely that he has personally enjoyed its carnal delights.

But the idea of falling in love with a courtesan is as alien to his mercantile mind as falling in love with an expensive kimono, or any other material object purchased with one’s own wealth. Hence, his bafflement and anger when Jirō proudly shows off Otsuru to him as his future bride. He is particularly annoyed when the courtesan Yaegaki points out to him Otsuru’s incompetence as a courtesan. From Echigoya’s viewpoint, Jirō has not only fallen head over heels for a piece of merchandise, but for a piece of defective merchandise.

Thus, although he feels uncomfortable about his role in the silk merchant’s destruction, he experiences no guilt over it. Jirō’s behavior, he believes, has gone far beyond the bounds of a respectable member of their class, for which, in the city man’s view, he has no one but himself to blame. One feels that, if Echigoya and Hyogoya (whose names cleverly “rhyme”) were to switch roles – with Hyogoya suddenly becoming a respectable merchant and Echigoya a brothel owner – each would do quite well in the other’s domain.

The only characters, besides the protagonist, who escape the filmmakers’ withering scorn are the workers in the factory at Yashu. They are loving and lovable people, totally dedicated to the success and happiness of their beloved boss. (Osaki is even shown alone in the factory at night, doing unpaid overtime at her weaving loom.) This idealization may well reflect Uchida’s and Yoda’s left-wing backgrounds. Nevertheless, these characters do not seem to me stereotypical; the filmmakers have given them enough dimension and complexity to seem real.

However, tragic ironies exist even in this benign world. Jiroku, Jirō’s servant, not only isn’t repelled by his master’s birthmark, he literally no longer sees it. He thus simply can’t grasp the fact that finding a beautiful young wife for his boss simply isn’t possible, despite the latter’s wealth and kindly personality. Ironically, Jiroku’s very bad advice to Jirō to rescind his marriage offer to Echigoya’s kinswoman – Jiroku thinks she’s too old – helps seal his master’s doom, because the latter unexpectedly turns to the toxic, predatory atmosphere of Yoshiwara for “true love.”

The silk merchant therefore becomes the victim not only of his own naiveté, but that of his servant. Thus, Jiroku’s grief at Jirō’s downfall, which he’s helpless to stop, is mixed with guilt for his unwitting part in it. This adds to the poignancy of the penultimate scene, when Jiroku and his bride-to-be, Osaki, weep inconsolably at the sad fate of their employer, who will soon be leaving their lives forever. Kataoka Eijirō, no relation to Kataoka Chiezō – the younger Kataoka had already shared the screen with the older one five years earlier, when he played the samurai Kojūrō in A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji12 – gives a very fine performance as this movingly conflicted character.

(Continued on page 3)