Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Other titles: Festival of Lakes and Forests (literal English title)

| Production Company | Tōei (Tokyo) |

| Scenarist | Uekusa Keinosuke |

| Source | Festival of Lakes and Forests (Mori to mizuumi no matsuri) [novel] by Takeda Taijun |

| Producer | Ōkawa Hiroshi |

| Cinematographer | Nishikawa Shōei |

| Art Director | Mori Mikio |

| Music | Kosugi Taiichirō |

| Editing | Soda Fumio |

| Sound | Komatsu Tadayuki |

| Performers | Takakura Ken (Kazamori Ichitarō, aka, Byakki [Phoenix]); Kagawa Kyōko (Saeki Yukiko, a painter from Tokyo); Mikuni Rentarō (Oiwa Takeshi, manager of the local fish-canning plant); Arima Ineko (Sengi Tsuruko, an Ainu bar woman); Fujisato Mayumi (Mitsu, an Ainu woman); Nakahara Hitomi (Shigeko, a young Ainu woman), Sato Yoshi (Sugita. a Japanese alcoholic, in love with Mitsu), Kitazawa Hyō (Dr. Ike, a Japanese anthropologist); Kōno Akitake (Dr. Kimura); Hanazawa Tokue (father of Shigeko); Usami Junya (Hanamori); Susukida Kenji (Oiwa’s father); Kazami Akiko (Oiwa’s wife) |

| Status | Extant |

| Photography | Color |

| Format | 35mm |

| Ratio | 2.35 : 1 (Tōeiscope) |

| English Subtitles | Yes / No1 |

| Original Release Date | November 26, 1958 |

| Length | 113 minutes |

| Awards and festival/retrospective screenings | Tokyo FILMeX (2004); BAMcinématek Uchida Retrospective (2008); MOMA Retrospective (2016) |

Note: I’ve seen this film with English subtitles only once, in 2016 during a screening at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) retrospective of Uchida’s films, where live subtitles were projected onto the screen. The copy I currently own of the film has no subtitles, and I don’t believe there currently exists any home video or streaming version with English subs. Therefore, many details of plot and characterization recounted here rely on my rather hazy memory of the narrative. On the other hand, seeing the film without subtitles enhances the viewing of it as a visual experience, which I will try to convey below.

Kazamori Ichitarō – better known by his nickname, Byakki (“Phoenix”) – a young militant activist belonging to the indigenous Ainu people, travels on horseback from village to village in Hokkaidō, Japan’s northernmost island. He distributes books and other gifts to the local children.

Meanwhile, during a traditional ceremony conducted by several elderly Ainu, two Shamos (Japanese) arrive by bus: Dr. Ike, a local anthropologist, and Saeki Yukiko, a young painter from Tokyo. Dr. Ike has been studying the Ainu for many years, and Yukiko, who is interested in drawing and painting Ainu subjects, is collaborating with him on one of his projects. They are both warmly welcomed by the locals.

During a train ride, Yukiko meets a middle-aged man, one of Dr. Ike’s Ainu friends. When they arrive at their destination, she is introduced to this man’s daughter: Shigeko, a pretty Ainu woman. Somewhat later, Yukiko, at the house where she is staying, attempts to paint Shigeko’s portrait, but is dissatisfied with the result. In a fit of impatience, she raises a knife to destroy the canvas, but Shigeko stays her hand.

Yukiko leaves the house for a short time and when she comes back, she finds that Shigeko has changed her mind and is about to destroy the painting herself. Yukiko stops her and the young Ainu woman, embarrassed, runs out of the house. The Japanese woman chases Shigeko through the streets, but at the dock, the girl finds her boyfriend in his motorboat and they both leave the dock before she can catch up to them.

Yukiko, crouching on the pier, is startled to see Byakki lying in a canoe in the water below, staring up at her menacingly. Without a word, he paddles away. While sitting near the shore of the lake, she is soon joined by Mitsu, an Ainu woman she had previously met at the local hospital. After chatting awhile, Mitsu relates her life story to Yukiko.

In a flashback, we see Mitsu as a young girl running with her younger brother from a policeman, having engaged in illegal fishing. Both seek shelter at the home of Sugita, a Japanese teacher sympathetic to the Ainu, and he protects them from the law. Later, the feelings between the young woman and the much older teacher deepen, and they become engaged.

However, before the wedding is to take place, Mitsu finds Sugita drunk and terrified, and no longer willing to brave society’s prejudice by marrying an Ainu woman. In revenge, Mitsu asks her younger brother to kill him. The boy enters the teacher’s hut with a spear and finds the man passed out from too much drink. Mitsu, after a change of heart, runs toward Sugita’s hut in panic, only to find the boy running out of it, as he could not bring himself to commit the murder, and she comforts him.

In the present, Yukiko returns to her house and discovers that her painting has been slashed. Shigeko then enters, and reveals that she never touched the canvas. The two women hear sinister laughter from outside the house, which Shigeko identifies as the voice of Byakki.

Yukiko goes to a tavern in the town, where she meets Sengi Tsuruko, a beautiful Ainu woman who is managing the bar. As they speak, half a dozen men from the local fish-processing business arrive, including Oiwa Takeshi, who manages the company for his father. The business is notorious in the area for its refusal to hire Ainu workers, and Tsuruko suffers rude comments (and some inappropriate physical contact) from the men because of her race. Also in the bar is Sugita, Mitsu’s former fiancé, who has become a hopeless drunk.

After all the men leave, Byakki, in a torn T-shirt, suddenly appears from a back room and helps himself to a drink. Yukiko is clearly attracted to him, but his reaction to the young woman from Tokyo is ambiguous. Tsuruko reveals to Yukiko that she had previously been married to the latter’s mentor, Dr. Ike. However, she had eventually realized that to the anthropologist she was no more than a living native artifact to be studied, which is why they divorced.

At the train station, Yukiko is approached by a young boy, Byakki’s friend, with a paper containing a message to convey to his enemies, the Oiwas. At the Oiwas’ house, not far from the seashore and their fish processing plant, she gives this paper to Takeshi’s elderly father, who, after she leaves, reads it and immediately burns it. The affable Takeshi, who treats Yukiko with unfailing courtesy, invites her to join him and some of his employees on their fishing boat. She sketches the men as they capture a large haul of fish.

At 5:00 PM, Takeshi’s father, as if suddenly understanding the meaning of Byakki’s message, runs out of the house and calls to his son in warning, just as he and his men are coming ashore after their fishing trip. Suddenly, there are several offshore explosions not far from where the men are standing, as Byakki approaches on horseback. As he passes Takeshi’s father, the Ainu rebel attacks him with a whip, injuring the old man’s head.

Infuriated, Takeshi fetches a shotgun from inside the house and, as Byakki approaches again, aims the gun at him. Yukiko, horrified, runs up to Takeshi and deflects his aim so that he misses, and the enraged Takeshi kicks Yukiko to the ground. As Byakki passes again, he lifts her onto his horse and the two escape together. Later, at home, Takeshi contemplates revenge against the Ainu activist.

Byakki brings Yukiko to a hut in the middle of a swamp. He gives her water and instructs her to remove her wet and dirty clothing and hang them up to dry and to put on his worn but clean trench coat. Something he says strikes her as funny and she responds with mocking laughter. Angered, he opens her coat and has sex with her.

The following day, Yukiko awakens alone and calls out to Byakki, who’s not there. Takeshi enters, his former courtesy towards Yukiko now completely vanished. He disdainfully throws into her lap a dagger in a sheath, as a challenge to Byakki.

Mitsu, in the hospital with a respiratory ailment, is awakened by Sugita, who has come with an apple as a peace offering. The two former lovers affectionately embrace, but Byakki enters and seizes Sugita. Byakki is Mitsu’s brother: it was he who had tried but failed to kill Sugita years earlier. He demands that Sugita leave the hospital room and the latter doesn’t resist. Meanwhile, Yukiko and the boy arrive at the hospital and give Byakki Takeshi’s dagger: a symbolic challenge to a final showdown between them.

Takeshi, near the shore of the lake, is performing target practice when the boy returns with the dagger – Byakki’s consent to the showdown – and a smiling Takeshi sends him back to Byakki. Yukiko doesn’t want him to fight Takeshi, but he’s made up his mind to do so. Yukiko, desperate, writes to Dr. Ike to persuade him to intervene.

On the appointed day, on a hill on an island overlooking the Bekanbe festival, with Ainu natives singing and dancing in their colorful costumes, Byakki with a rifle slowly approaches Takeshi, who’s similarly armed. Meanwhile, Dr. Ike and Yukiko arrive on the island by boat and rush on foot to the place where the two men are fighting. Takeshi shoots and seriously wounds Byakki in the left side of his face. Byakki attacks Takeshi, stabbing him in the leg with a dagger. He nearly strangles Takeshi, but the latter informs his attacker that he knows Byakki is not actually a full-blooded Ainu, but has Shamo blood, to Byakki’s evident distress.

With the boy’s help, Byakki prepares a tourniquet for his enemy’s leg while removing the dagger. When Dr. Ike and Yukiko arrive, he tries to shield the sight of his bloodied face from them. Although Yukiko, who’s carrying his child, still wants him, he flees in his canoe. Finding Sugita’s corpse in the lake, the conscience-stricken Byakki pulls it out of the water and places the body face up near the bow of the vessel. He rows away, never to be seen again by his people.

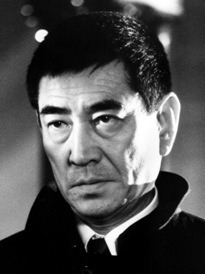

Takakura Ken was, with Mifune Toshiro, one of the two most iconic Japanese male movie stars, though unlike Mifune – who achieved his breakout role in Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel (Yoidore Tenshi, 1948) only a year after his debut in 1947 – it took Takakura nearly a decade of constant work to achieve superstar status. Born Oda Goichi, he graduated from Meiji University in the 1950s. He only began his film career in 1955, when he impulsively auditioned at Toei Studios, after he had intended to apply for a managerial position. In many of his early films, and also much later, he frequently appeared as a swaggering, brooding tough guy within the popular yakuza genre. His performance as an escaped convict in the classic 1965 adventure film Abashiri Prison (Abashiri Bangaichi), directed by Ishii Teruo, is widely considered his breakthrough. During his 56-year career, he won the Japan Academy Prize for Best Actor four times, more than any other performer. Because of his English-language skills, he was also one of the very few Japanese actors to enjoy success in Hollywood, appearing in Robert Aldrich’s World War II film Too Late the Hero (1970), Sydney Pollack’s The Yakuza (1974), Ridley Scott’s Black Rain (1989) and Fred Schepisi’s Tom Selleck vehicle, Mister Baseball (1992). For Uchida, Takakura went on to star as Musashi’s nemesis Sasaki Kojirō in the final three installments of the five-part Miyamoto Musashi series (1963-1965), as a hard-boiled police investigator in A Fugitive from the Past (Kiga kaikyo, 1965) and as a yakuza in the director’s penultimate film, Hishakaku and Kiratsune: A Tale of Two Yakuza (Jinsei-gekijô: Hishakaku to Kiratsune, 1968). He died at age 83 in 2014.

Kagawa Kyōko, one of the most distinguished of all Japanese actresses, is now (as of December 2022) one of the last living links to the Golden Age of Japanese Cinema whose career is still active. After graduating from high school in 1949, she began her film career the following year. She is one of the very few performers – Tanaka Kinuyo was another – who appeared in works by all of Japan’s “Big Four” directors: Mizoguchi Kenji (Sansho the Bailiff (Sansho Dayū) and A Story from Chikamatsu (Chikamatsu monogatari), both 1954); Ozu Yasujirō (Tokyo Story (Tokyo monogatari, 1953)); Naruse Mikio (Ginza Cosmetics (Ginza Keshō, 1951), Mother (Okasan, 1952), Lightning (Inazuma, 1952), Sudden Rain (Shu-u, 1956) and Anzukko (1958)); and, especially, Kurosawa Akira (The Lower Depths (Donzoko, 1957), The Bad Sleep Well (Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemura, 1960), High and Low (Tengoku to Jigoku, 1963), Red Beard (Akahige, 1965) and Madadayo (1993)). She has also given memorable performances in films by many other distinguished directors, such as Tanaka Kinuyo, Toyoda Shirō, Inagaki Hiroshi, Yoshimura Kōzaburō and Koreeda Hirokazu, as well as in the famous kaiju film Mothra (Mosura, 1961) by Honda Ishirō. Kagawa, who works now mostly in television, has received many awards for her work from the Japanese government.

Arima Ineko began her acting career with the famed Takarazuka all-female stage troupe; appropriately, she made her film debut in 1951 with a movie called Mrs. Takarazuka (Takarazuka fujin), directed by Oda Motoyoshi. She is known in the West almost exclusively for two films she made in her youth for Ozu Yasujirō: Tokyo Twilight (Tōkyō boshoku, 1957), in which she played a delinquent, and Equinox Flower (Higanbana, 1958), as the rebellious daughter of the protagonist. This is unfortunate, because she appeared in many other important films for distinguished directors, such as the dramas Late Chrysanthemums (Bangiku, Naruse Mikio, 1954) and Snow Flurry (Kazabana, Kinoshita Keisuke, 1959), the first film of the classic antiwar trilogy The Human Condition (Ningen no joken, Masaki Kobayashi, 1959) and the mystery thriller Zero Focus (Zero no shōten, Nomura Yoshitarō, 1961). She was particularly memorable in Imai Tadashi’s classic Night Drum (Yoru no tsuzumi, 1958). For Uchida, she would go on to portray the prostitute Umegawa in Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (Naniwa no koi no monogatari, 1959). In 1961, Arima married her co-star from that film, Nakamura Kinnosuke; they divorced four years later. She has continued acting on and off, mostly on television, into the 21st Century; her most recent acting credit was in 2019.

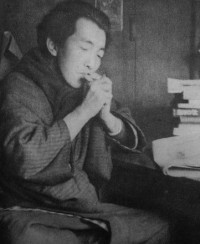

Uekusa Keinosuke, an almost exact contemporary of his friend Kurosawa Akira – they were born 18 days apart in March 1910 – was an elementary-school classmate of the future director. (In his autobiography, Kurosawa vividly describes their friendship, as well as their similarities and differences of temperament.) Appropriately, he is best known in the West as the screenwriter for two of Kurosawa’s postwar films of the 1940s: One Wonderful Sunday (Subarashiki nichiyōbi, 1946) and, especially, Drunken Angel, the film that made Mifune Toshirō a star. He also wrote the screenplays for Gosho Heinosuke’s Once More (Ima hitotabi no, 1947) and Ieki Miyoji’s excellent antiwar film, All Our Children (Minna waga ko, 1963), as well as co-authoring the script for the early anime Alakazam the Great, a.k.a., Journey to the West (Saiyūki, 1960). He published an autobiographical novel, Winter Flower Yuko (Fuyu no Hana Yuko), which was nominated for the Naoki Prize in 1973 and was later twice adapted into television movies. He died in 1993, age 83.

(Continued on page 2)