Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 3)

As one might expect, the use of music in this film is not conventional.1 In fact, there are disconcertingly long periods in which no music at all is heard – an innovation in the context of movies at this time.

However, a scene that takes place during a summer drought, and which begins with the community gathered in the temple to pray for rain, includes on the soundtrack a hypnotic, percussive rhythm, involving a drum and some sort of metallic-sounding instrument. This music then carries over into the subsequent scene in which Kanji and Otsugi are shown carrying heavy buckets of water from the river to their lands to keep their crops from perishing. The music very dramatically emphasizes this harsh, brutal, grinding toil. I can’t remember a single work from the 1930s in which sound was used in quite this way. To my mind, it recalls Takemitsu Toru’s experiments with musique concrète in such works as the 1964 film Kwaidan.

Another unusual use of music is the incongruously mournful sound of the wedding singer during the night marriage sequence. However, I can’t be certain if this song was created by the composer, or whether Uchida utilized a traditional folk melody and performer.

The only time music is used in a conventional way is during the ferry scene, in which the composer creates a lovely, wistful tune on a wind instrument (flute? recorder?), accompanied by violin and harp, to convey Otsugi’s loneliness at the sight of her friends’ departure to work in the mill. (See the Contact page for a video clip of this scene.)

This is a very tricky film to recommend, because it can’t be denied that the movie in its present degraded condition is often very tough to sit through. This difficulty is not helped by the fact that the English subtitles of the German print were translated not from the Japanese dialogue directly – which is spoken in a hard-to-understand local dialect, even for most Japanese2 – but from the print’s hard-coded white German subtitles, many of which, because these appear against a bright white background, are completely illegible (and thus can’t be translated into English). Therefore, at least fifty percent of the original dialogue remains untranslated in the version I have seen.

However, it’s very probable that even for the original Japanese audience watching the pristine print that was first screened in Tokyo in 1939, the film’s bleak subject matter, dark cinematography and unusual (for urbanites) spoken dialect didn’t make for easy viewing. That the movie was nonetheless a success would seem to indicate a strong collective desire for a new kind of screen realism, one that would not gloss over the painful or disturbing aspects of the lives of marginalized and socially invisible Japanese.

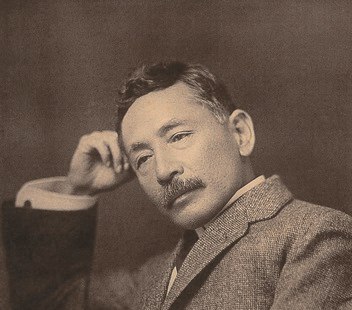

But I’m also pretty sure there would be some viewers even today who’d react to this film in much the same way that the famous writer Natsume Soseki did when he first read and reviewed The Soil as a favor to the dying Nagatsuka. In his introductory essay for the book’s 1912 publication, Natsume expressed utter repugnance towards the novel’s village and its people. (“Their lives are like those of maggots hatched out of the soil” is a representative sentence.)3 Natsume was not wrong, in the sense that the world of this tale is indeed a nasty, primal, ungentle one. But it’s also a world in which responsibility, generosity, love and even joy are not unknown. Uchida, like the novelist before him, depicts these characters as all too human, with their flaws as well as their virtues uncensored.

Despite the difficulties presented by the film’s physical deterioration, it demands multiple viewings to get past its rough patches – and the confusion caused by its missing scenes4 – in order to fully grasp its harsh beauty and epic power. Some later Japanese films resemble Earth in superficial ways. For example, Shindo Kaneto’s The Naked Island (Hadaka no shima, 1960) was almost certainly influenced by it, and certain passages in Kurosawa’s work, particularly in Seven Samurai, strongly echo it.5 But no work that I know of in the Japanese tradition is quite like it.

Earth is sometimes regarded as a far-right-wing movie. This view seems to me very strange, since I’ve seldom seen a film in which the economic exploitation of farm laborers has been so realistically and painfully depicted. I also think it significant that the only surviving prints of the film were located in the archives of two former Iron Curtain countries, East Germany and Russia, which seems to me to imply that this film at some point enjoyed a left-wing audience in Europe.

So it appears entirely plausible that Uchida, perhaps not quite consciously, deceived the Government’s censors. Because the character of the protagonist has been made so unpleasant, which seems to imply that Kanji’s troubles are his fault alone and not that of the social order, and because the film glorifies the peasant “folk” – a concept promoted by both far-left-wing and far-right-wing ideologies – Uchida may have been able to pass off a very subtly Leftist film as a pro-nationalist one. But a definitive judgment probably must wait upon the (admittedly, highly unlikely) discovery of a watchable print of Uchida’s complete two-hour-and-twenty-two-minute version.

A month before this movie was released, the Japanese Parliament passed the infamous Film Law. This legislation put all future cinematic production under the authority of the government.6 Henceforth, until the end of the war, filmmakers, who now had to be licensed, not only were forbidden to contradict official national policy – the kokutai – but were increasingly forced, on pain of official censure or even arrest, to actively promote that policy to the degree possible. Documentary filmmaker Kamei Fumio was later jailed for a year for allegedly defying national policy with his films.7

Donald Richie was right when, in The Japanese Movie, he called Uchida’s Earth “one of the finest films of the decade and a summation of all that the Japanese cinema had come to represent in the 1930s.”8 During that decade, the first generation of Japanese directors, of which Uchida was one of the leading lights, created the standard of high craftsmanship and artistic seriousness by which all subsequent Japanese films – even those of the Golden Age of the 1950s and early-to-mid-1960s – would be measured. But although some good and even great films continued to be made in the period both immediately preceding and during the Pacific War, these became fewer and further between as the war went on, in the overwhelming atmosphere of gloom and oppression that had descended upon the country.

Despite the film’s damaged, incomplete and hard-to-watch existing print, no lesser rating could possibly be appropriate for this astonishing cinematic achievement.

MUBI – (Dan Sallitt) [Full discussion of the film]

MUBI – The Ferroni Brigada [Extensive discussion of the film, as well as other Uchida works]

Senses of Cinema (Alexander Jacoby) [Includes a brief discussion of Earth]

Wonders in the Dark – (Allan Fish) The late Mr. Fish reviewed the German video, noting its poor condition and citing it as a Magnificent Ambersons-like ruined masterwork. He makes a few significant errors, such as referring to the character of Otsugi as Kanji’s wife rather than his daughter, but his genuine astonishment and enthusiasm for the work comes through.

Film Comment (Mark Walkow) [Includes a paragraph about the film]

Festival Archives (Max Tessier) [Includes a brief description of Earth, as well as a revealing quote by Uchida (see above)]

[…] adaptation of Nagatsuka Takashi’s novel The Soil, though he wasn’t cast in Uchida’s 1939 film version. After making his movie debut in 1936, he amassed over 250 film and TV credits over six decades. […]

[…] Uchida's Earth (土), his 1939 masterpiece Aug 2, 2021 / 12:21 pm Reply […]

[…] literary adaptation and the first of two Uchida films in three years (the second one was Earth (Tsuchi)) to top the KJ poll. The ultimate origin of this work was a published story by, of all […]