Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 5)

As we’ve noted already, Uchida’s health was seriously compromised when he returned to Japan in October 1953. But he’d also compromised himself politically, from the film industry’s point-of-view, by helping the Communist revolution in China. (Curiously, Japan’s film executives apparently had no problem with the fact that he’d also once worked for the child-killing, Fascist sociopath Amakasu.) Fortunately, neither family nor friends deserted him, despite his desertion of them and his reputation as a Leftist radical. His wife publicly stood by him, though privately, because he had left her alone for nearly a decade to raise their children on her own, the couple’s relations had become – and were to remain – strained.1

More importantly, from the perspective of Uchida’s career, his colleagues in the industry rallied round him. The camaraderie evident in that 1936 Japan Film Directors Society photo had not been destroyed by the war. Uchida in his hospital bed worried about what his first film after his long hiatus might be,2 but the decision was soon taken out of his hands.

One of the six major studios, Toei, had hired Uchida’s old colleague Shimizu Hiroshi to direct a remake of a film that Uchida’s late friend Inoue Kintarō had filmed in the 1920s: A Traveler’s Journey of Sorrow (Dochu Hiki, 1927). Shimizu passed the reins of the project over to his friend Uchida, who took over as director.3 To do so, Uchida had to sign a contract with Toei, which proved not to be a problem, as that studio, far more than its five competitors, eagerly welcomed filmmakers with leftist reputations. This was particularly true for those who had worked at Manei, since Manei veterans Negishi Kan’ichi (who, as already noted, had served as head of that studio before Amakasu) and Makino Mitsuo were now in charge at the new studio. As film scholar Yomota Inuhikō states, “We could even say that Manei’s legacy served as the undercurrent for Toei.”4

Furthermore, Shimizu, along with two other great filmmakers of Uchida’s generation, Ozu Yasujirō and Itō Daisuke, volunteered to serve as credited “advisors to the production” on the new film.5 This provided a kind of “seal of approval” for Uchida, reassuring audiences (and perhaps the film industry as well) that the director they had all so admired in the 1930s was now ready to make more masterpieces. For Kishi, this gesture demonstrated “their sincere desire to help him recover” after his ordeal.6

The story of the making of A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji, 1955) is recounted in greater detail in my review of that film. Suffice it to say, the picture was a hit, and the critics, in the annual KJ poll, selected it as the eighth best film in a highly-competitive year. Kishi saw the movie and admired it, but thought it revealed that Uchida was “conflicted,” noting the ironic – and anachronistic – use of the patriotic World War II song “Umi Yukaba” on the soundtrack in the film’s final scene.7

Also according to Kishi, Uchida’s success aroused resentment among some people who had shared his tribulations in China. They’d all gone north from Hsinking with the Communists largely on Uchida’s say-so, because of their great respect for him. But now that the survivors had finally returned to Japan, they were all blacklisted as Communists by the film industry, while the famous Uchida was excused and allowed to resume his career. Uchida was deeply conflicted about this contradiction as well.8

Immediately after directing this movie set in the feudal era, Uchida filmed – and released in the same year, 1955 – two movies set in contemporary Japan: the comedy-drama-musical-allegory Twilight Saloon (Tasogare Sakaba) and the domestic melodrama A Hole of My Own Making (Jibun no ana no nakade). These were made for Shintoho and Nikkatsu, respectively. (The latter was to be his final film for his prewar “home” studio.) It’s unclear why he was allowed to do this, since he was apparently already signed to Tōei.9 What is clear was that his creative range was even broader than ever before, as he released, in the same year, three fascinating films in three totally unrelated genres, which were also, apparently, quite different from any films he’d previously made.

As far as I know, Uchida’s commercial and creative rebound was the most impressive comeback of any filmmaker in the entire history of Japanese cinema. The only one comparable to his, in my opinion, was when Kurosawa, after a decade of turmoil – which included several aborted projects, a major flop and a suicide attempt – released in 1975 his Oscar-winning Russian-language hit, Dersu Uzala. However, Kurosawa had the great advantage of a very large international audience for his work, which Uchida never had… and still doesn’t.

From this point on, the biography of Uchida literally becomes the story of the making of his films. Though he was rapidly approaching old age, he seemed determined to make up for the enforced idleness of his more than decade-long “lost period” (1943-1954), and he was astonishingly prolific. During 1956, 1957 and 1958 – the year he turned 60 – he released six single films and the first two parts of a trilogy: eight individual releases in all. Feudal dramas predominate in this list, but Uchida, again demonstrating his amazing range, also made two acclaimed movies set in contemporary times that were totally different from one another: a 1957 suspense thriller about trapped miners, The Eleventh Hour (Dotanba), which was voted the seventh-best film of the year in the KJ critics’ poll, and an “eastern Western,” the stunningly-photographed The Outsiders (Mori to mizuumi no matsuri, 1958), a social-justice drama set among the oppressed, indigenous Ainu people in the beautifully rugged northernmost Japanese island, Hokkaido.

But even among the jidai-geki movies of these years, there’s considerable variety. The Horse Boy (Abarenbo kaido, 1957) is an inspired children’s film with a memorable boy hero, played by Ueki Motoharu, the son of one of Uchida’s favorite stars, Kataoka Chiezō; Alexander Jacoby calls it one of Uchida’s most underrated films.10 Disorder in the Kuroda Clan (Kuroda Sodo, 1956) movingly depicts the dilemma of the persecuted Japanese Christians of the 17th Century. The 1956 film, Rebellion from Below (Gyakushu gokumon toride: literally, Counterattack at the Prison Gate Fortress), which I haven’t seen, sounds particularly intriguing: it’s a drama of class warfare set at the end of the samurai era, based on the legend of William Tell.11 And The Thief Is Shogun’s Kin (Senryo-jishi, 1958), which I also haven’t seen, deals with the theme of the “royal double,” which Kurosawa would later tackle in his acclaimed film, Kagemusha (1980).

Finally, there’s Uchida’s first color film, the three-part tragedy Sword in the Moonlight, a.k.a., The Great Bodhisattva Pass (Daibosatsu tōge: Part I, 1957; Part II, 1958; Part III, 1959). The protagonist of this series is the most relentlessly “anti” antihero in the history of Japanese literature, or perhaps of any literature: the sociopathic samurai Tsukue Ryūnosuke, created by the novelist Nakazato Kaizan. Two multipart versions of Nakazato’s epic had been previously made: in the mid-1930s by Inagaki Hiroshi, and in 1953 by Watanabe Kunio for Toei. (Uchida’s leading actor, Kataoka Chiezō, had starred as Tsukue in the second of these two.) And two other adaptations of the novel, starring Raizō Ichikawa and Tatsuya Nakadai (the Nakadai version being the only single-film variant among all these versions), would be released after Uchida’s trilogy.

I’ve seen the Nakadai version, The Sword of Doom (Daibosatsu tōge, 1966), directed by Okamoto Kihachi, and though that movie is perhaps more visually exciting than Uchida’s series, Uchida’s take on the villain/hero communicates much better what the critic Sato Tadao considers the whole point of the narrative: not the character’s evil, but his suffering and its expiation.12 This trilogy is the first multipart Uchida film to survive – he’d made several in the prewar era – and it demonstrates his remarkable skill with epic narrative. It was a talent he would display again in the even longer Miyamoto Musashi series of the early-to-mid-1960s.

From his youth, Uchida had always been fascinated by theater. Beginning in the late 1950s, he made a trilogy of films based on Japanese classical drama, beginning with Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (Naniwa no koi no monogatari, 1959) and A Hero of the Red Light District (Yōtō monogatari: hana no Yoshiwara hyakunin-giri, 1960), and concluding in 1962 with the strangest and most stylized of all his surviving films, The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi), which we’ll discuss in the following section. However, these films are not simply performances of existing dramatic works; they are about performance, or rather about Japanese society as performance, both in the feudal past and, by analogy, in contemporary (turn of the 1960s) Japan.

In Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka and A Hero of the Red Light District, Uchida mastered his “classical” style, as opposed to his “realist” (Earth) and “mannerist” (Unending Advance) styles: a highly formal, elegant, polished and distanced approach, with a very striking yet somehow restrained use of color. However, this stylistic distancing doesn’t mute the emotional impact of these works; indeed, in the case of Hero, it serves to make the cruel, devastating narrative bearable. (Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka was voted the seventh-best film of 1959 in the KJ poll.)

Another Uchida work from this period, the minor comedy-drama The Master Spearman (Sake to onna to yari, 1960),13 isn’t based on a play, but it, too, is about a performance. When, because of court intrigue, the master of a samurai named Kurando is forced to commit seppuku, Kurando himself is put under extreme pressure by his clan to follow suit. There follows a hilarious scene in which the samurai attempts to carry out his ritual suicide as an outdoor sporting event, complete with vendors selling “Kurando dumplings” to the bloodthirsty crowd. The ironic and comic climax of this scene illustrates, as effectively as would Kobayashi Masaki’s much more somber film Harakiri (Seppuku, 1962), released two years later, the irrationality and emptiness of the samurai code.

A mysterious film from this period merits mention: Voyage to Patagonia: Crossing the Great Glacier (Nanbei Patagonia tanken: daihyoga o yuku, 1959), Uchida’s only extant documentary. Apparently, the elderly filmmaker never ventured to the South American ice fields in which the movie was shot. Other filmmakers had captured all the spectacular location footage that Uchida edited into a feature, for which he then received a director’s credit. Since Uchida was not a documentarian, this film, which I’ve not yet seen, is, like the 1925 animated short Tale of Crab Temple referred to earlier in this essay, a complete outlier in the artist’s filmography.

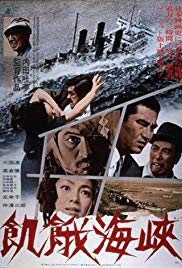

In the years 1961 to 1965, Uchida completed only three projects: the gigantic five-part Miyamoto Musashi saga (1961-1965), which was perhaps his most commercially successful and definitely, at nine-and-a-half hours, his longest work; his weirdest film, The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi, 1962); and his most acclaimed movie ever, the epic noir melodrama, A Fugitive from the Past (Kiga kaikyo [literally, “Straits of Hunger”], 1965). Along with Earth, A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji and, perhaps, Police Officer, those three works are the ones upon which his reputation in the West – to the extent he can even be said to have one – rests.

Although the Miyamoto Musashi series was very popular in Japan, it’s not, in my opinion, one of the finest Uchida films. Though made in the same “classical” style as Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka and Hero of the Red-Light District, it seems to me much less innovative and cinematically exciting than either. (As Stuart Galbraith IV has noted in his commentary for the DVD box set of the films, Uchida, during the making of this series, was suffering from prostate problems that led to severe back and leg pain, and thus his work on it probably hastened his death.)14 Nakamura is an excellent Musashi and most of the rest of the cast is also fine, particularly Mikuni Rentarō as the priest Takuan, Kogure Michiyo as the randy bandit-widow Oko and veteran actress Naniwa Chieko as Musashi’s comic nemesis Osugi.15 But it seems to me like the kind of commercial assignment that a talented director agrees to take on in return for the opportunity to film more personal projects.

Certainly The Mad Fox was a very personal project for Uchida. An adaptation of an early 18th Century play, the film seems to be an homage to theatricality itself. Bunraku, Kabuki, Noh and avant-garde stage styles are freely mashed together in this demented piece of folklore about a female fox who falls in love with a human and bears his child. (The English-language title, by the way, is all wrong, because it’s the human hero who’s insane, not the fox.) This movie takes Uchida’s “mannerist” or perhaps “Expressionist” style as far as it would ever go, into the realm of the surreal. (If the great Spanish filmmaker Buñuel had seen this film, I think he would have loved it.) But at heart, despite its playfulness, the movie is a tragedy of evil triumphant, and of irreparable trauma and loss.16

Oddly similar in its examination of evil and trauma, though much more realistic, is A Fugitive from the Past, Uchida’s most-praised masterpiece in his native land. In a 1999 Best-Films-of-All-Time poll published by Kinema Junpo, it ranked, remarkably, as the third-greatest Japanese film ever, below Seven Samurai and Naruse Mikio’s Floating Clouds, but above Tokyo Story. In a similar poll that the magazine published ten years later, the film had slipped somewhat to a still-impressive 16th place, higher than, for example, Kobayashi’s Harakiri (17) and Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (24).17

The high regard of Japanese critics is justified, because A Fugitive from the Past is, in a way, the director’s most surprising achievement. As Alexander Jacoby notes, with this work, the sixty-six-year-old Uchida assimilated the style and approach of Japanese New Wave directors such as Imamura Shohei – an artist nearly thirty years his junior. Indeed, Jacoby claims, I think rightly, that Uchida with this work improves upon the work of the younger director, “better[ing] Imamura as a study of the dark underbelly of postwar society.”18

Uchida achieves here a remarkable fusion of his realist and mannerist styles. A number of scenes resemble clips from a horror movie, and he made them that way not from any impulse to shock, but to depict “realistically” his guilt-ridden protagonist’s tortured soul. At several points in the film, the film image literally “goes negative”: a remarkable evocation of hell.

As Craig Watts has noted, and as we have confirmed in the section about the filmmaker’s China adventure included above, Uchida had been strongly influenced by Mao’s famous essay On Contradiction, in which the Communist leader theorized that, in modern Capitalist societies, contradictions build upon each other gradually, until eventually there is an explosion (most often a revolution), in which the contradictions are resolved. In this movie, the contradictions of postwar society set the antihero, Inukai, played by Mikuni Rentarō, on a collision course with the prostitute Yae (Hidari Sachiko), leading to tragedy and a kind of expiation. Mikuni and Hidari, both great actors, would never be better than they are in this film, and the supporting cast, which includes the young Takakura Ken, more than holds its own with the two leads.

There is a fascinating religious undercurrent in the film as well. The ex-policeman obsessed with catching and punishing Inukai, Yamisaka (Ban Junzaburō), is curiously adept at chanting Buddhist sutras, and the beautiful final scene evokes a kind of Buddhist peace, as if sin itself had been (temporarily) purged from the world. It’s a remarkably strange and moving conclusion to what many believe to be Uchida’s greatest work.

(Continued on Page 7)