Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Alternate Titles: Crab Temple Omen (literal English title); A Lenda do Templo do Caranguejo (Portuguese)

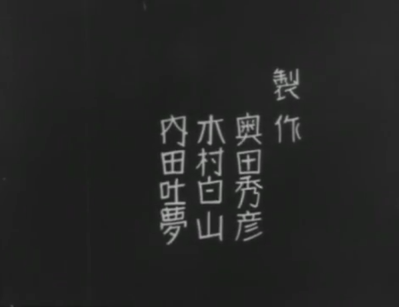

| Production Company | Asahi Kinema Gomei-sha |

| Co-directors | Kimura Hakuzan (or Hakusan); Okuda Hidehiko1 |

| Scenarist | Unknown |

| Cinematographer | Fujii Shizuka2 |

| Type of Film | Animated short (silhouette animation) |

| Status | Extant3 |

| Photography | Black and white |

| Sound | Yes: musical score added (YouTube version) |

| English subtitles | No (Japanese intertitles) |

| Original release date | 1924 or 1925 (exact release date unknown) |

| Length | 11 minutes (1 reel) |

| Archival Location | National Film Center, Japan (now National Film Archive of Japan (NFAJ)) |

| Festival / retrospective screenings | International Animation Festival Hiroshima (2016) |

A man rings a temple bell. A young woman in a long gown is standing in a garden picking flowers when an old man, her father, appears. Together they leave, with the woman still carrying the flowers, and go to a temple to pray with other worshipers, as is their custom.

Meanwhile, a boy finds a live crab on the ground, picks it up and proceeds to torment it by pulling its legs off. Returning from the temple, the old man berates the boy for abusing the crab, but the boy refuses to stop torturing the animal. The young woman pays the boy to give her the crab, and after he does so and walks away, she sets it free.

In autumn, when the rice is plentiful, the old farmer and his daughter are working in the fields. The old man sees a snake capture a live frog in its mouth. The farmer protests the snake’s cruelty and, not really understanding what he’s saying, he promises the snake that he can marry his daughter if he releases the frog. The snake sets the frog free and goes away.

The snake is then seen in a ravine with the skeletons of animals nearby. The snake magically turns into a man, and with a wave of his fan, he turns the animal skeletons into a vulture-like skeleton-bird, which flies away. The skeleton-bird lands near the house where the woman and her father live, and the snake-spirit magically reappears in its human form.

The snake-man knocks on the door, demanding the woman in marriage that he was promised, but her father won’t let him in. The farmer asks him to return in three days. The snake-spirit tells the old man that his life won’t be worth living if he reneges on his promise, and vanishes into thin air. The father and daughter cry in despair and pray to Buddha for help.

The third day arrives. In the middle of the night, the bird and the snake-man return and the latter knocks on the door again. When neither the farmer nor his daughter let him in, the spirit, resuming his snake form, enters the house and then changes again into his human form. Meanwhile, many crabs, in gratitude for the woman’s earlier kindness to one of their own, begin to converge on the house to protect her.

The snake-man seizes the woman, but she hits him with a sutra scroll… which he condemns as unfair. Enraged by the woman’s rejection, he resumes his snake form, apparently intending to kill her. But the numerous crabs attack the snake and by dawn they have defeated it. The dead snake is seen hanging from the branch of a tree, at the foot of which are a number of crabs who lost their lives in the battle.

The woman and the old man give a prayer of thanksgiving at their household shrine. A temple is built at the request of the farmer and his daughter, dedicated to the crabs that saved the woman from the snake.4

Kimura Hakusan was a pioneer Japanese animator, active in the 1920s and 1930s. His mentor was another animation pioneer, Kitayama Seitarō, and Kimura worked at Kitayama’s own studio, which was destroyed in the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. He then went on to make films at Asahi Kinema Gomei-sha, where he collaborated with Uchida. With Masaoka Kenzō, he developed the first Japanese animated talkie, Chikara to Onna no Yo no Naka (1933, lost). He is also said to have made the first Japanese pornographic cartoon, Suzumi fune (1932). His birth and death dates are unknown.

It’s entirely characteristic of the head-scratchingly bizarre career of this filmmaker that his earliest extant film as director (actually co-director) isn’t a fiction feature, or even a live-action short, but a work of animation, despite there being no evidence whatever that he was trained as an animator. This is the first of two “what the hell” works in Uchida’s filmography. The other is a documentary (his only one) Voyage to Patagonia: Crossing the Great Glacier (Nanbei Patagonia tanken: daihyoga o yuku), which he released in 1959, right after the final installment of the Great Bodhisattva Pass trilogy, but just before Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka – quite a busy year for a 61-year-old man.5

Even more unusual is the fact that this is a work of silhouette animation. This rare form, consisting simply of black cardboard cutouts “moving” against a white background – the technique is much, much harder to master than it sounds – had a brief vogue in the 1920s, because of the popularity of the work of German animator Lotte Reiniger. What’s particularly fascinating is that Reiniger’s masterpiece The Adventures of Prince Achmed (Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed), the earliest feature-length animated movie of any kind to survive into the present, was originally released in 1926. So whether one dates Tale of Crab Temple as a 1924 or a 1925 film (sources differ), it definitely predates the classic German feature. According to the Nishikata Film Review site, which specializes in the history of Japanese animation, another early animator, Ōfuji Noburō, was also said to have been inspired by Reiniger during this period, so it seems that the German filmmaker was quite influential among her Japanese peers even before she released her most famous work.

For me, the movie raises a number of questions on a purely narrative level. Aren’t the woman and the old man both taking this religious thing about reverence for crabs and frogs to extremes? And even if the old man truly wants to save the life of the frog, isn’t offering to the snake a woman in marriage – the man’s own daughter, for heaven’s sake – an overzealous way of doing so? And if the snake can assume human form whenever it wants, why doesn’t it do so to catch the frog more easily?

As with so many fairy tales, it just doesn’t make sense to examine the tale’s logic: in most cases, there isn’t any, even if one chooses to suspend one’s disbelief in the supernatural. One simply responds, or not, to the charm of the narrative… and this narrative has considerable charm. The filmmakers realistically depict the little boy’s glee in tormenting the crab. The skeleton-bird, which transports the snake-spirit, is a memorable creation. The scene of the terrified old man hiding from the snake-man in a rat-infested trunk is quite amusing. And it’s very interesting that the woman fights back physically (with a sutra scroll!) against the snake, while a close-up allows us to witness her look of distress and anger as she does so. Even at this early stage, Uchida was depicting strong female characters with sympathy.

At just slightly less than one reel, the film is exactly the proper length for this material. And the music score provided in the YouTube video version – obviously not composed for the original release – is quite pleasant.

The Buddhist content of this film is presented playfully and lightheartedly, in much the same spirit that Reiniger treats the stereotyped Orientalist elements in The Adventures of Prince Achmed, so that even now, it’s almost impossible to be offended by Uchida’s (or Reiniger’s) humor. But many years and a World War later, Uchida, in such films as A Fugitive from the Past, explored Buddhist ideas of karma and atonement quite seriously indeed. (Uchida is buried in a Buddhist temple.)

In much the same way, the filmmaker early in his career added vaguely Leftist ideas to his satirical comedies – such as Sweat or the lost A Human Puppet, both 1929 – to give them edge. But in later life, he structured his plots much more carefully under the influence of complex Marxist and even Maoist concepts. So with both Uchida’s religious and political journeys, what started out as a kind of game became a kind of fate.

This film had no influence on modern-day anime, which it doesn’t remotely resemble, so its historical significance is limited. And of course, this work is a collaboration between three artists, so we cannot safely attribute any single aspect of the film to Uchida alone. But I can’t help but regard this movie as the earliest example of how effectively Uchida could tell a story. For this reason alone, it remains a fascinating work for Uchida fans.

For additional notes on Uchida’s ongoing interest in animation, see my review of The Mad Fox, another film in which animals turn into humans and back again.

This charming – though, for many reasons, extremely odd – short work of silhouette animation, Uchida’s earliest extant film, provides a likable but atypical example of his prewar work.

Nishikata Film Review (unlike IMDB and JMDB, this site dates the film to 1924; they also give important biographical information about co-director Kimura)

A trailer to Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed

I’m excited to find this site. I want to to thank you for your time just for this fantastic read!! I definitely appreciated every little bit of it and i also have you saved to fav to look at new stuff on your website.