Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

From time to time, I will interrupt my series of reviews of the films of Uchida Tomu to post general observations on Uchida, his current reputation and his art.

Photo above: A snapshot of six Japanese film directors, taken in 1955. Uchida Tomu is seated in the middle, bottom row. Ranged around him, from lower left, are: Gosho Heinosuke (1902-1981), Ozu Yasujirō (face partially obscured) (1903-1963), Ushihara Kiyohiko (1997-1985), Kosugi Isamu (1904-1983) and Naruse Mikio (face partially obscured) (1905-1969). Kosugi was also an actor who performed in many of Uchida’s films (the last being Twilight Saloon, released in the year this picture was taken, 1955), including several of those which I have cited below.

If one looks at Uchida’s filmography, one can’t help but notice that there are a lot of films from the prewar and war eras that are missing and presumed lost.1 (Fortunately, there are no lost movies in the director’s postwar (1955-1970) career, though some of these – such as The Thief Is Shogun’s Kin (Senryo-jishi, 1958), or the 1959 documentary about Patagonia – are extremely hard to see.) For me, this fact raises an intriguing question: if I could wave a magic wand to uncover a treasure trove of previously missing Uchida films, in watchable prints, which works would I most want to find there? The discovery of any missing Uchida movies would, of course, constitute an important find, but there are some I’d be more eager to see than others, based on descriptions of them found in books and on websites.

From the list below, I have omitted any Uchida films that definitely exist, even if in incomplete form, such as Theater of Life: Youth Version (Jinsei gekijo: Seishun hen, 1936, which I haven’t yet seen), Unending Advance (Kagirinaki zenshin, 1938), and Earth (Tsuchi, 1939). (Locating a complete version of any of these movies would be wonderful, however.) The works in the list appear in reverse order of preference.

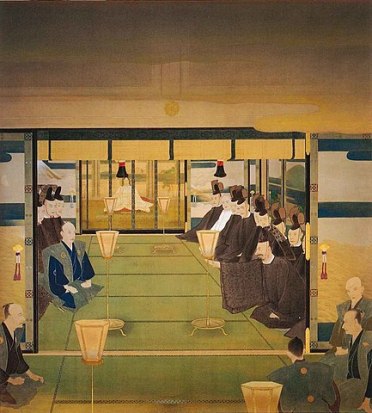

This trilogy of films was the first work Uchida Tomu made after his prize-winning Earth (1939). It, too, won a prize when the first of the three parts was chosen as one of the “Best Ten” films of 1940 by Japanese critics in the annual Kinema Junpo poll (at seventh place). This marks the true beginning of Uchida’s accommodation with the prewar military government, as it relates the story of a formerly rebellious samurai of the 19th Century who becomes a willing agent of the Meiji government after the restoration of the Emperor. Here is Yomota Inohiko’s description of this lost film, presumably derived from 1940s sources:

“In 1940 to commemorate the so-called kigen – the twenty-six hundredth year anniversary founding of Japan by the mythical first emperor Jinmu – Uchida paired up with the cameraman Yokota Tatsuyuki to shoot the three-part series History (Rekishi). The film is set at the end of the Edo period and offers a lyrical portrait of the life of a samurai from the Aizu domain. A soldier in a rebel army just before the Meiji Restoration, he finally comes to be a merchant in his hometown, before heading off to the Seinan War as a police officer of the new government.”

Yomota Inohiko. What is Japanese Cinema? A History, p. 66. Columbia University Press, 2004, tr. Philip Kaffen. ISBN: 9780231549486 (Kindle).

Based on the above description, this movie would seem to take the ideology of Police Officer into a 19th Century narrative, with a stronger pro-government emphasis. Despite its apparent propagandistic intent, I wish it still existed for us to watch today, partly to compare it with the 1933 film, and also partly to see how successfully Uchida handled an epic tale in the prewar era, since he would tackle such extended narratives in two postwar series: the three-part tragedy Sword in the Moonlight (Daibosatsu tōge) (1957-1959) and the five-part Miyamoto Musashi saga (1961-1965).

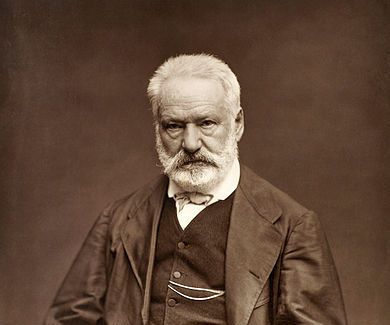

Victor Hugo’s classic Les Misérables has always been very popular in Japan, and it’s been adapted by Japanese directors many times. (The Internet Movie Database counts three adaptations that were released just in the decade prior to this two-part work.) This silent film, named after the book’s protagonist, Jean Valjean – or “Jan Barujan,” as the Japanese pronounce the name – is the first-ever multipart work that the director filmed by himself alone, so it’d be very interesting to see this first attempt by Uchida at a long narrative. A surviving copy of the work would also put paid to the common but erroneous claim that the director, during this early period, focused exclusively on comedies.

The cast list shown on IMDB also cites several actors with whom Uchida would work again, including Yamamoto Kaichi and Miake Bontarō, both of whom would later appear in Earth (as the old grandfather Ukichi (Uhei) and the farmer Heizo, respectively). It would be particularly interesting to see Yamamoto in a role other than the elderly peasant he plays in Earth. My guess is that he may well have portrayed a role corresponding to the bishop who, in the novel, makes Jean Valjean a present of the candlesticks that the authorities arrest Valjean for stealing. (It’s also possible that he played the villain of the piece: the pathologically relentless Inspector Javert.) However, I can’t be sure which role he played, because the only cast list I’ve found for this film shows just the actors’ names and not the names of the characters they portray.

But most of all, I’d like to see this picture because the narrative of Uchida’s 1965 masterpiece, A Fugitive from the Past (Kiga Kaikyō), though based on that of a Japanese novel by Minakami Tsutomu and not upon Hugo’s work, bears a very strong resemblance to Les Misérables. In both works, for example, a criminal assumes a new identity and reinvents himself as a pillar of society. I would love to have the chance to compare this film with that much later work to try to determine how much Uchida’s worldview changed over the years.

Peter High, in his indispensable book The Imperial Screen, gives a tantalizing description of this “full-fledged military spectacular”:

“The experiment was a tripartite omnibus directed by Tasaka Tomotaka, Abe Yutaka and Uchida Tomu. Starting with the premise that ‘war has been the human condition for tens of thousands of years,’ it hypothesizes a war on the Asian mainland. Conflicts of the past, present and future are treated in alternating segments (much like Griffith’s structuring for Intolerance). In the ‘future’ segment, directed by Uchida, an unnamed country from the east (the United States?) suddenly assaults Japan by air. Osaka is devastated by a rain of bombs, but superior air defenses wipe out the attacking force. The Japanese tank corps, along with the film’s two heroes, swiftly carry the battle to the enemy homeland. Although the heroes are bitter rivals in love and business in the ‘present’ segment, the battle teaches them to reconcile their differences. At the very end of the film, this future segment is revealed to have been merely a cautionary tale for the two rivals. Back in the present, they dedicate themselves to weapons research and look hopefully toward the brighter day that is sure to dawn.”

High, Peter B., The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931-1945, pp. 11-12. University of Wisconsin Press (Madison), 2003. ISBN: 02990181340 (paperback).

The above description makes this picture seem like a commercially surefire hit in the war-plus-romance genre popular at the time (and long afterwards) in so many countries, but the film, surprisingly, tanked. “Despite the film’s star-studded cast [including Uchida’s usual stars of the time, Shima Kōji and Kosugi Isamu] and impressive corps of directors – even Mizoguchi Kenji is included as ‘advising director’ – the film sank into almost instant oblivion. It rates no mention in standard film histories, and only detailed program notes and a few stills remain today.”2

The sheer scope and ambition of this project is intriguing. And though the result was a work of blatant nationalist propaganda (and may have failed, in the largely pacifist pre-Manchurian War era, for that very reason), I can’t help but wonder what such a movie – which strongly reminds me of a later work of speculative propaganda, the British film Things to Come, authored by none other than H.G. Wells – might have looked like.

This was probably far from the first parody of the samurai film subgenre of jidai-geki movies. Uchida’s contemporary, Itami Mansaku, who specialized in period-film satire, had begun directing in 1928, three years before this film was released. But Uchida’s film seems to have been the first such film to capture the attention of Japanese critics, as it was voted the sixth-best movie of the year in the Kinema Junpo poll for films released in 1931.

In this story, Uchida apparently didn’t just poke fun at certain stock character types, but mocked the entire established conventions of the revenge film genre. Several moviemakers of the time, most notably Itō Daisuke, critiqued feudal values by creating strong “nihilistic” heroes at odds with the rigid authoritarianism of that time. But Uchida, like Itami, took another tack, and condemned feudal values by ridiculing them.

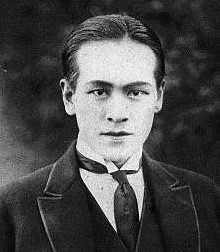

Another reason that I would very much like to see this movie is that it provided a very early role for one of the Japanese screen’s greatest actresses: Yamada Isuzu, who had only made her debut the previous year, in 1930, and was all of 14 years old when she made this picture. Yamada would go on to glory, doing stellar work for many great Japanese directors, including all of the Big Four: Mizoguchi (in the 1930s), Kurosawa (in the 1950s and 1960s), Naruse and Ozu.

A little over a quarter-century after The Revenge Champion, she and Uchida would team up one last time when she gave a wonderful performance as a high-born lady in the first of his two Chikamatsu adaptations, The Horse Boy (Abarenbo kaido, 1957).

Uchida’s first prize-winning film – it placed an impressive fourth in the Kinema Junpo critics’ poll for films released in 1929 – this movie seems to have been a much more barbed satire of class and capitalism than the extant Sweat, released later in the same year. A comedy about a capitalist con man who, in the words of Anderson and Richie, “rises in the world by cheating and is in the end cheated by society,”3 it was also a very important film in Uchida’s history, quite aside from its popularity with the critics, as it seems to have been the first film in which he advocated, through the use of satire, strongly left-wing views.4 In fact, the film came to be associated with the keikō eiga (“tendency film”) movement of the time. (See my review of Sweat for a detailed description of this short-lived genre.)

According to a translation of this Japanese blog, contemporary critic Iijima Tadashi said that the film was “outstandingly splendid” among recent Japanese movies, “a thing that has never been seen in Japanese movies until now” and that it “has materials and ideas that are truly suitable for modern life.” He went on to say that it used foreign cinematic techniques that were so appropriate to the subject matter that they went unnoticed by the audience.5

The irony of this situation is that Uchida admitted in his memoirs that he had made the film solely because he was assigned the project by Nikkatsu. The original novel, serialized in a newspaper, by the radical writer Kataoka Teppei (a member of the Proletarian Film League of Japan, or Prokino) had been popular, so the studio wanted to cash in on it by buying the rights and assigning one of its best and most reliable directors, Uchida, to adapt it. (His regular screenwriter of the time, Kobayashi Masashi, composed the script.) Ironically, it was only after the success of this film that Uchida began exploring left-wing theories and ideas in earnest. This film was thus the beginning of a process by which Uchida would become one of the most politically sophisticated (and ideologically complex) of all Japanese directors.

By all accounts, this was a very special movie. It was voted the fifth best film of the year by critics in the Kinema Junpo awards, and Uchida’s admiring colleague during his China years, the editor Kishi Fumiko (see my biography of Uchida), cites this as a film that especially impressed her, and made her proud to be working alongside him.6 Casting both his regular male leading players of the time, Shima Kōji and Kosugi Isamu, Uchida tells the sad story of the sudden impoverishment of a well-to-do man:

“[The story was] about a merchant who acts as guarantor for a friend’s debt and loses everything when the friend fails to pay. In an attempt to regain some of his losses, the merchant goes to a moneylender. When he is refused, the moneylender’s wife takes pity on him, offering him milk to feed his hungry cat. This the cat refuses; it too turns against the unfortunate man. At last, however, he pulls himself together and opens a small street-stall. The first half of the film was very cinematically achieved and became something of a model for further films, for a time being regarded as a standard for literary adaptations. The latter half, however, with its ungrateful cat, sharply betrayed its opening style and was consequently less effective.”

Anderson and Richie, op. cit., p. 121.

According to Joseph A. Anderson and Donald Richie, this film, because of its realism, was “a landmark in the junbungaku movement,” which advocated for the adaptation into cinema of acclaimed contemporary Japanese literature to make films more relevant to modern social realities.7 In Richie’s book, The Japanese Movie, there’s a wonderfully evocative production still from the film, with the hero standing at night, looking skyward, in what looks to be an alley in a shantytown.8

Also notable about this film was the fact that all music and sound effects featured on the soundtrack were “diegetic,” that is, they originated within the world of the film and were thus heard by the characters as well as the audience. The composer Fukai Shirō particularly praised this aspect of the film: “It is interesting for me that the Japanese films seen as today’s masterpieces, Sōbō [Many People, Kumagai Hisatora, 1937], Hadaka no machi, and Aienkyo [The Straits of Love and Hate, Mizoguchi Kenji, 1937], are the ones which do not require what we call [accompaniment] music.”9

Interestingly, Uchida never permanently abandoned “accompaniment” (i.e., non-diagetic) music, utilizing brilliantly-written scores in such postwar films as Hero of the Red-Light District and A Fugitive from the Past. So it would be very interesting to see what Uchida did with sound during this era, when talkies were still new and he was experimenting with eliminating non-diagetic music altogether.

I haven’t given up hope that these and other movies by this director may one day see the light of day. However, it should be noted that it’s not true, as many articles have implied, that the surviving output of this director is sparse. Uchida’s extant films – counting the multipart ones – are in quantity comparable to Kurosawa Akira’s 30-odd films. So if we never find that cache of lost cinematic treasures, we cinemaphiles would still have much to be thankful for.