Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 2)

Inserting Chikamatsu as a character in an adaptation of one of his own plays (actually two, counting the Kabuki work adapted from his puppet play) is a clever trick, rather like placing William Shakespeare in the middle of Verona in a film version of Romeo and Juliet. (I’d be very interested to know whether this idea was Uchida’s or if it was an invention of the screenwriter, Narusawa.) This conceit turns out to be more than just a stunt, though, as the great author is presented by the filmmakers in an intriguingly ambiguous way. Within the floating world, the playwright is depicted as a universally respected figure because of his art – a kind of feudal version of a media celebrity. But he’s really more like the pathetic whore Umegawa than anybody but he himself realizes.

When the very same magnate who “courts” the courtesan offers to fund Chikamatsu’s theater, the writer is not at all happy with the offer but can’t refuse, because like almost all theater people everywhere, his living is a precarious one. And when the drunken magnate publicly humiliates Umegawa, Chikamatsu sneers but does not protest. He silently empathizes with the unhappy woman, but never openly challenges the social order upon which both his life and his art depend.

In certain ways, the Chikamatsu character is rather like the Stage Manager in Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Because of Kataoka’s wonderful performance, he immediately establishes a rapport with the movie audience, but his presence, like that of Wilder’s character, is also vaguely unsettling. Chikamatsu is not merely observing, like a benign but dispassionate deity, everything that happens between the young couple. (His ubiquity strains belief, but the viewer only realizes its unlikelihood when thinking about the film afterwards.) He’s also subtly directing the audience’s attention and its sympathies, creating an ironic frame around a story that could easily have become mawkish or overwrought without such artistic distancing.

In the film’s final act, it becomes less and less clear how much of what we’re seeing is real and how much is happening in the playwright’s mind. A very dramatic scene in which the fugitive lovers, hiding out in Chubei’s mother’s hut in the snow-covered countryside, try to decide whether or not they should separate, is immediately followed by a shot of Chikamatsu in Osaka lying down with his eyes closed, as if Chikamatsu had dreamed up the whole sequence we’ve just witnessed.

The concluding Kabuki dance that Nakamura and Arima perform together is marvelously staged. (See the featured image at the top of this article.) Both actors had theater backgrounds: Nakamura in Kabuki and Arima with the famed Takarazuka all-female acting troupe, so they both understood the stylized and presentational aspects of traditional drama. The dance is a wonderfully effective way for the film to transition to the puppet performance with which the narrative appropriately closes. But it also serves as a startling contrast to the chaotic scene (a flashback memory of Umegawa’s) in which the lovers are brutally apprehended by the authorities and cry out each other’s names as they’re literally torn from one another.

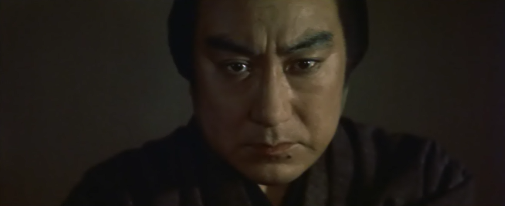

The tight close-up of Chikamatsu that ends the movie (with an evocatively slow fadeout) is rich in ambiguous meaning. To what is the playwright’s scornful scowl directed? To the floating world? To Osaka and its mercantile culture? To the audience? To himself, as a writer who cynically exploits the sufferings of two hapless young people for his own artistic and commercial gain?

A possible clue can be found in Umegawa’s screams of anguish on the soundtrack, which drown out the sounds of the puppet performance. To the audience of the play, the tragedy of Chubei and Umegawa, transformed into art, is a beautiful and edifying spectacle. But to the young people themselves, it means the end not only of their happiness but of their lives: literally in Chubei’s case, figuratively in that of Umegawa, who will survive, but only to become a sexual automaton. So perhaps that close-up of Chikamatsu is meant to represent Uchida himself, who perceives the grim legacy of this cruel, ugly world in the greed and complacency of the Japan of his own century.

Many of the supporting players, familiar from other movies of the era, do truly outstanding work. The star actress Tanaka Kinuyo gives a typically nuanced and poignant performance in the minor role of Myokan, the stern merchant widow undone by her naïve trust in her adopted son. (A tragic play could definitely be written from her point-of-view.) As Hachi, the man who gets Chubei into so much trouble by dragging him against his will to the pleasure quarter, Chiaki Minoru effortlessly evokes the character’s lazy decadence and amorality.

Hanazono Hiromi portrays Myokan’s luckless daughter, Otoku, with sensitivity and intelligence. Shindo Eitarō, as the ruthless pimp Jiemon, adds yet another memorable villain to the long list of disreputable characters he had created for Mizoguchi and others. But perhaps best of all these actors is Naniwa Chieko as Oen, the old woman who acts as a go-between among the courtesans on behalf of the procurers. With her fixed death’s-head grin and bizarrely stylized movements, Ms. Naniwa’s character perfectly personifies the robotic emptiness that is Uchida’s vision of the world of the brothel… and of the corrupt city beyond it.

The film is one of the best examples of Uchida’s postwar “classical” approach, a style distinct from both the flamboyant realism of Police Officer and the Expressionist fantasy of the last hour of The Mad Fox. The film is very efficiently and effectively edited: in a work with a running time well under two hours, Uchida (as implied by the necessarily very long synopsis above) packs in a remarkable amount of plot information. We get all the clues we need about the characters, including the subtlest nuances, yet the narrative never feels rushed or fragmented.

Uchida and his cameraman, Tsuboi Makoto, utilize camera movement elegantly, but almost never in a superfluous or overly showy way. In the scene in which Chikamatsu witnesses Umegawa bandaging the little girl’s finger (and then being humiliated for this by the magnate), the director makes skillful and subtle use of crane and dolly shots to define the space and the relations between the characters. The color cinematography throughout is dazzling, but is nonetheless employed ironically, to display the deceptive glamour of the “floating world” that conceals beneath it so much brutality and suffering.

It’s instructive to compare this adaptation of a work by Japan’s greatest playwright with two cinematic adaptations of that same writer by Mizoguchi Kenji and Shinoda Masahiro.1 All three films engage in complex artistic dialogues between theatrical artifice and various levels of reality. In Mizoguchi’s A Story from Chikamatsu (Chikamatsu monogatari, 1954), the director attempts a more-or-less realistic treatment of a lesser-known work by the playwright, with moments of necessary unreality – a studio water tank, for instance, standing in for Lake Biwa – occasionally interrupting, but not greatly marring, the illusion of the real. And Mizoguchi’s trademark long-shot-one-take style is a compelling substitute for the stylized conventions of Bunraku.

Uchida’s film begins with puppet play aesthetics presented obliquely, as a stage performance seen in long shot, within the context of the very human Chikamatsu’s struggle to keep his theater afloat. But Bunraku conventions slowly start to dominate the narrative, as the already doll-like movements and primary-color emotions of the young lovers give way to images of the characters as dancing human dolls, which in turn are replaced by literal dolls acting out an imaginary version of the real-life tragedy.

In Shinoda’s film, Double Suicide (Shinju: Ten no Amijima, 1969), the mythical fourth wall is completely broken down, with no attempt to establish an illusion of what anybody would recognize as reality, historical or otherwise. That film begins as anti-naturalistically as possible, with a recorded phone call in which Shinoda himself discusses with his co-screenwriter how he thinks the film we’re watching should end, with images of Bunraku puppets being assembled and manipulated by professional puppet masters (kurago).

In these three cases, the approach each filmmaker takes is very different. In the Mizoguchi film, the emphasis is moral: the wicked patriarch – the almanac-maker played by Shindo Eitarō – is destroyed by his greed and lust, while his wife and her lover miraculously triumph in death. In Uchida’s film, the emphasis is social and political: the courtesan and the courier are crushed by a vile system that fatally favors the crass and the corrupt over the innocent. In the Shinoda work, the emphasis is psychological: the characters are defeated by their own irrational desires and an only partly-grasped death wish.2

All these themes, on paper anyway, resonate with me, but only the first two works move me deeply, whereas the Shinoda film, except for its bleak, powerful ending, leaves me almost totally cold, despite brilliant cinematography and some intriguing ideas, such as casting the same actress, Iwashita Shima, as both the hero’s wife and his courtesan-lover. And if I had to choose one of them as the most successful artistically, I would probably pick the Mizoguchi. But I think it’s only marginally superior to Uchida’s film, as repeat viewings have only deepened my love and appreciation for this wonderful work.

Uchida’s brilliant take on the classic Japanese theater boasts an imaginative playfulness that rescues it from the reverential stiffness so common to adaptations of classic literature in Western cinema.

Window on Worlds (Hayley Scanlon)

Senses of Cinema (Alexander Jacoby) [brief mention of the film]

IFFR (International Film Festival Rotterdam) (2005)

MOMA Retrospective (2016 retrospective)

World Cinema Paradise (John David Baldwin) [Includes my brief review of the film]

[…] in this film, she starred in The Body (Ratai), directed by Uchida screenwriter Narusawa Masashige (Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka). She also appeared in the final installment of Inagaki Hiroshi’s Miyamoto Musashi (a.k.a., […]

[…] Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (Naniwa no koi no monogatari; 浪花の恋の物語), 1959 […]

[…] in 1959, right after the final installment of the Great Bodhisattva Pass trilogy, but just before Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka – quite a busy year for a 61-year-old […]

[…] Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 警察官), 1933A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji; 血槍富士), 1955Twilight Saloon (Tasogare Sakaba; たそがれ酒場), 1955Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (Naniwa no koi no monogatari; 浪花の恋の物語), 1959 […]

[…] over 250 film and TV credits over six decades. For Uchida, he would later appear in Dotanba (1957) Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (1959), The Master Spearman (1960) and the fourth installment (1964) of the five-part Miyamoto […]

[…] Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 警察官), 1933A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji; 血槍富士), 1955Twilight Saloon (Tasogare Sakaba; たそがれ酒場), 1955Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (Naniwa no koi no monogatari; 浪花の恋の物語), 1959 […]

Hey, I think your mostly on target with this, I wouldnt say I totally agree , but its not really that big of a deal .

Based on your comments, I assume you’ve seen the film. Just out of curiosity, though you say it’s not a big deal, what precisely don’t you agree with?