Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 1)

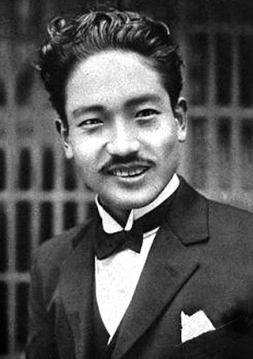

Kataoka Chiezō was a period-film star who began his career as a young man in the 1920s and remained extremely popular into middle age and beyond. A Kabuki-trained stage actor, he signed with Makino Productions in 1927, but was such a hit that only a year later he established his own independent production company, which was more successful than any of the other major stars’ production companies. Eventually, he joined Uchida’s studio, Nikkatsu, in 1937, but didn’t work with the director at that time. In the 1950s, he signed with Tōei. After acting for Uchida in this film, he made seven more pictures with him: The Kuroda Affair and Rebellion from Below (both 1956), the Swords in the Moonlight trilogy (counted as one film) (1957-1959), Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (1959), The Master Spearman (1960), the final film in the five-part Miyamoto Musashi series (1965) and, most memorably, Hero of the Red-Light District (1960). Kataoka eventually made over 200 films, and died exactly one day after his 80th birthday in 1983.

Katō Daisuke was one of Japan’s most beloved character actors, his round face and portly figure instantly recognizable to the Japanese film audience. After making his debut in Yamanaka Sadao’s Priest of Darkness (Kōchiyama Sōshun, 1936), he was frequently cast in both period roles and modern ones, and was equally adept at playing ruthless thugs and likable salarymen. For Uchida in the same year, 1955, he would play a right-wing ex-soldier in Twilight Saloon. He was a particular favorite of Kurosawa, appearing prominently in Rashomon, Ikiru, Seven Samurai (as Shichirōji), Yojimbo, etc., and he eventually became a relative-by-marriage of the great director when his son, Haruyuki, married Kurosawa’s daughter, Kazuko. He died in 1975.

Tsukigata Ryūnosuke was a star of the prewar and wartime eras who remained active as a supporting player after the war. He became very popular in jidai-geki movies in the 1920s and appeared as Gonpachi in the original version of this film, A Traveler’s Journey of Sorrow (Dochu hiki, 1927), now lost. Thus, he served as one of only two living links between the original movie and the remake. (Sugi Kyōji, who plays a very small role in this film as a lord, had also appeared in the earlier film as Genta.) For Uchida, Tsukigata appeared again in Rebellion from Below, the Swords in the Moonlight trilogy, The Mad Fox and the second part of the Miyamoto Musashi series (1962). For Western audiences, his most famous role is as the villain, Gennosuke, in Kurosawa’s debut film, Sugata Sanshiro (1943). He died in 1970, age 68.

Shindō Eitarō was one of Japan’s finest character actors. Beginning his film career in the early 1930s, he became associated early with Mizoguchi Kenji, and eventually made a dozen movies for that director, almost invariably playing villains. His most famous role was as the title character in Mizoguchi’s masterpiece film, Sansho the Bailiff (Sansho Dayū, 1954). After A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji, Shindō would collaborate three more times with Uchida: on The Horse Boy (1957), The Thief Is Shogun’s Kin (Senryo-jishi, 1958) and Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (1959). He died in 1977, age 77.

Ueki Motoharu and Ueki Chie were the son and daughter, respectively, of the film’s star, Kataoka Chiezō (whose real-life surname was Ueki). Chie would later have a small role in Uchida’s Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (1959). Motoharu would go on to act several times more for Uchida: in Rebellion from Below (Gyakushu gokumon toride, 1956), The Eleventh Hour (Dotanba, 1957) and, very memorably, as the title character in The Horse Boy (Abarenbo kaido, 1957).

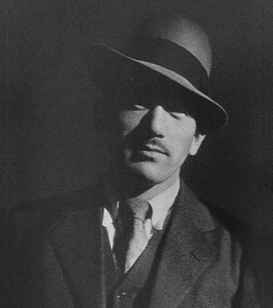

Yokoyama Unpei is reputed to have been Japan’s first professional film actor. In 1899, as an 18-year-old stage performer, he was cast as a policeman in a now-lost film – lasting approximately one minute – recreating the recent apprehension of a notorious real-life criminal: Shimizu Sadakichi, the Pistol Robber (Pisutoru gōtō Shimizu Sadakichi). Since he was portraying a character (though in a recreation of an actual event) and as all prior known Japanese films had been mere recordings of stage performers (e.g., kabuki players, dancing geisha), Yokoyama had probably given the first-ever professional performance by an actor in a Japanese-produced movie. He would resume film acting a dozen years later, and eventually appeared in over 250 movies. During the prewar era, he had been cast in Uchida’s only partly-extant Theater of Life: Youth Version (Jinsei gekijo: Seishun hen, 1936). His final appearance would be in the all-star spectacular Chūshingura (1962) by Inagaki Hiroshi. He died in 1967 at age 86.

Yoshida Sadaji was a cinematographer who collaborated frequently with Uchida in the postwar period. In addition to this film, he worked for the director on Rebellion from Below (Gyakushu gokumon toride, 1956), The Kuroda Affair (1956), The Horse Boy (1957), Hero of the Red-Light District (1960), The Mad Fox (1962) and the third, fourth and fifth parts of the Miyamoto Musashi series (1963-1965). He also worked on films directed by Gosha Hideo, Kudō Eiichi and Fukasaku Kinji (e.g., the famous Battles Without Honor and Humanity (Jingi naki tatakai) series). He died in 2018 at the age of 100.

This is one of four films directed by Uchida whose production history rivals the work itself in dramatic interest. The other three are Earth (Tsuchi, 1939), A Fugitive from the Past (Kiga kaikyō, 1965) and his final movie, Swords of Death (Shinken shōbu, 1971).

When Uchida returned to Japan in October 1953 after his long Chinese adventure, his career was, for several reasons, in very serious trouble. It had been eleven years since he’d released a movie – not a negligible gap for any filmmaker even now, and certainly not in the Japan of that era, when directors were extraordinarily productive. Ozu Yasujirō, who at the end of the war returned late to Japan from an American prisoner of war camp, nevertheless had resumed his career in the spring of 1947 with Record of a Tenement Gentleman (Nagaya shinshiroku), and had already released five other movies by the time his friend Uchida set foot again on his native soil. (A sixth, the classic Tokyo Story (Tōkyō Monogatari), would come out only a few weeks after Uchida’s return.)

Just as concerning was the obviously fragile state of Uchida’s health. A photograph of the director on the day of his homecoming shows him looking at least a decade older than his 55 years and walking with the aid of a cane. He was immediately hospitalized upon arrival.

The third reason, and not a minor one, was political: his long stay in Communist China had made him suspect within the increasingly conservative film industry. Particularly after the devastating Toho strikes of the late 1940s, directors with strongly Leftist convictions, such as Imai Tadashi or Yamamoto Satsuo, generally had a much tougher time than apolitical or even right-wing directors in getting their films made. And in the view of the industry, Uchida had gone beyond even those two younger artists by having actively aided and abetted Mao’s revolution. (Strangely, the studios seemed to have no problem at all with the fact that Uchida had earlier worked for the Fascist child killer, Amakasu Masahiko.)

Fortunately, the management at Tōei, a then-new company, was quite accommodating to veterans of Man’ei (the Manchurian Film Association), even those with Leftist ties like Uchida, as explained by film historian Yomota Inuhiko:

Tōei was newly established as a production company in 1951, with Man’ei’s Negishi Kan’ichi jumping on board. Negishi brought in his former colleagues, who had returned from the continent, one after another as film personnel, putting Makino Mitsuo in charge of production. He did not hesitate to welcome leftist film personnel who had been abandoned by other companies during the red purge, including Imai Tadashi, Sekigawa Hideo and Ieki Miyoji. We could even say that Man’ei’s legacy served as the undercurrent for Tōei.1

So in a sense, Uchida had no choice about the studio to which he should sign. A decade and a half later, in the late 1960s, Uchida and Tōei would part ways acrimoniously, but not before he had made over a dozen films – including several masterpieces – for that most commercially-minded of film companies.

Even more important to Uchida’s future than the welcoming arms of Tōei were his old filmmaking friends from the 1930s, who now all rallied round him. Thus, the fraternal spirit displayed in that old Japan Film Directors Society photo from 1936, to which I alluded in my biography of Uchida, turned out not to be illusory. Tōei had originally assigned Shimizu Hiroshi, not Uchida, to the Bloody Spear project, but Shimizu gallantly stepped aside to turn the director’s chair over to his older and needier friend. And Shimizu would also stick around to serve as an official “advisor to the production,” along with Ozu Yasujirō and Itō Daisuke. (Itō would much later write the script for Uchida’s final film, Swords of Death.)

This support was crucial. These highly-respected filmmakers were all putting their names on the line (and in the movie’s opening credits) to vouch for Uchida’s genius… which they, to be brutally honest, couldn’t really have been certain was still there. And it’s reasonable to assume that they were also on board to reassure a nervous industry that Uchida would not try to turn the project into a film version of the Communist Manifesto – though in truth Itō, for one, was still as left-wing as Uchida had been back in the 1930s. It may have been yet another attempt to set the studio’s mind at ease when Uchida made his well-known comment to production head Makino that he intended to make “a peaceful movie” out of this remake of his deceased friend Inoue Kintarō’s 1927 film, A Traveler’s Journey of Sorrow (Dochu hiki).

So the period immediately following Uchida’s return to Japan was surprisingly similar to the beginning of his professional life in the early 1920s, in the sense that he was once again able to leverage personal relationships into a viable career – only this time under vastly different and much stranger circumstances.

(Continued on Page 3)

[…] A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji; 血槍富士), 1955 […]

[…] Saloon (Tasogare Sakaba; たそがれ酒場), 1955A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji; 血槍富士), 1955Police Officer (Keisatsukan, 警察官), 1933The Mad Fox (Koiya koi nasuna koi; […]

[…] four have received more than 200 votes on the Internet Movie Database: A Fugitive from the Past, A Bloody Spear on Mount Fuji, Hero of the Red-Light District and the first film in the five-part Miyamoto Musashi series.) I […]

[…] a very rough sketch for the neurotic young samurai Sakawa in Uchida’s first postwar masterpiece, A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (1955). But the tragic consciousness that Uchida brought to his depiction of that complex character […]

[…] Kikushima Ryūzō (book) and television film Dotanba (1956)1 […]

[…] after the Occupation to condemn or at least question feudal authority, as he did most famously in A Bloody Spear at Mt. Fuji (Chiyari Fuji, 1955), was working within an existing tradition rather than breaking with that […]