Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from Page 2)

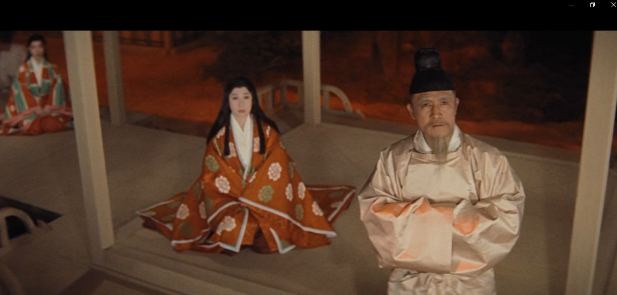

Like Uchida earlier films derived from theatrical source material, such as Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka and Hero of the Red-Light District, this film is notable for its flamboyant use of color. But there’s an almost hallucinatory vibrancy in its use here that seems to me unique to this director’s work. The first image that the viewer sees, following the brief spoken prologue and credits sequence, shows the Imperial sages gathered in a courtyard, their robes and even their faces appearing bright blood-red from the light produced by the recent eruption of Mount Fuji, as they gaze worriedly at the red sky above them. (I assume that this effect was achieved simply by placing red filters over the studio lights.)

When the scene shifts to Yasunori’s residence, we see the astrologer, the ladies-in-waiting and his adopted daughter Sakaki also gazing up at the scarlet-colored sky. (Even the pond where the fish swim appears to be red, as if the fish were bleeding.) But the white-clad Yasunori, almost supernaturally, appears to give off a silver glow unlike the others, symbolizing his close association with supernatural forces. It is noteworthy that of these characters, only Sakaki and her lady-in-waiting are dressed in the same blood-red color as the sky – an ominous sign.

At Yasuna’s first appearance, and then for the entire first part of the film, he wears masculine robes in a neutral shade of blue, denoting his traditional role as lover and protector. But after he fails to save Sakaki and loses his mind, Yasuna, with his now effeminate movements and gestures and unkempt long hair, and wearing the dead woman’s red robe, has taken on the feminine attributes of Sakaki – almost as if he’s replaced her.1

He dances in a field of flowers that are not merely yellow, but bright saffron: the color, so to speak, of his madness. When he collapses with the robe over his head, the red garment becomes a kind of temporary shroud. And when he awakens later, we see that the field in which he had been dancing was bare and without flowers, yellow or otherwise.

However, in the scenes that take place in the woods – the foxes’ domain – the dominant colors are, logically, brown and ocher, in which Yasuna and Kuzo-no-ha, in their bright clothing, appear dangerously conspicuous and vulnerable to Akuemon’s attack. However, later, in the cave-like house in which Kon tends to the wounded Yasuna, successfully protecting him from his enemies, the fox-girl’s drab-colored garments and even her “fox face” fall away, as she transforms herself into an image of the human Kuzo-no-ha in all her splendor.

At the very end, when we return, like a musical reprise, to the scene in which Yasuna dances in the meadow, negating everything we’ve just seen as mere fantasy, the brilliant saffron flowers have become the color of death itself – Yasuna’s impending death – and Sakaki’s red robe has become a permanent shroud, as he falls to the ground and dies, presumably of malnutrition. (Paradoxically, he thus eludes both Iwakura and Dōman, who had wished to track him down and kill him like a hunted animal.) The final shot is the only one almost totally devoid of color, except for the flame representing the fox-spirit world – as if that animistic world was the only reality and the court and its vicious, scheming humans were mere illusion.

In 1956, the year after Uchida’s remarkable comeback, his studio, Toei, purchased a small animation company and renamed it Tōei Dōga Co., Ltd., later known internationally as Toei Animation Company. Toei, flush from recent successes, harbored the ambition of turning its new animation unit into the Japanese equivalent of Disney. To achieve this, it hired a number of bright young talents, including Takahata Isao and, shortly after, Miyazaki Hayao, both later to become world-famous after they founded their own legendary anime company, Studio Ghibli.

Around 1960, Uchida had suggested to Toei the idea of making an animated version of Japan’s oldest extant folk tale, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (Taketori Monogatari), which was written early in the 10th Century, the same era in which The Mad Fox is set. (It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Uchida was interested in animation: as we’ve noted, the very first extant film for which he was credited as a director is the 1925 silhouette-animation short subject, Tale of Crab Temple (Kaniman-ji Engi).) The young Takahata, along with several others at the studio, was asked to submit a report detailing the approach he thought the studio should take in adapting this ancient story into an animated film.

Nothing ultimately came of this project at the time. But Studio Ghibli producer Suzuki Toshio has claimed that the creative strategy Takahata had wanted to adopt in 1960, as described in that original report, was exactly the same approach the director took when adapting the material for his own 2013 masterpiece (and final film), Kaguya-hime no monogatari (The Tale of the Princess Kaguya). The 21st Century anime therefore had a gestation period of over fifty years.

So during the production of The Mad Fox, when Uchida needed to depict the kitsunes’ world in the film – in scenes other than those in which he simply employed actors wearing fox masks and imitating the movements of Bunraku puppets – he naturally turned to Toei Animation to create it. In the scene in which Kon tries to save Yasuna, who’s been set upon by the villainous Akuemon’s hunters, the viewer sees flames in the distant woods that are miraculously transformed into animated figures of leaping foxes, hurrying to aid their human ally.

The effect, however, seems to me startlingly crude and unmagical. I would have to agree with Keiko I. McDonald, who calls Uchida’s use of animation in this scene “puzzling” and maintains that its appearance mars the intended pathos of the dramatic situation.2 It should be borne in mind, though, that animation in Japan at that time was still in its journeyman period, decades away from the astonishingly sophisticated techniques for which it would become world-famous, through the work not only of Studio Ghibli, but of such artists as Oshii Mamoru and the late Kon Satoshi.

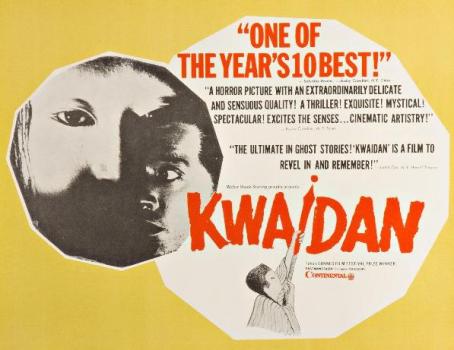

Anyone who has seen both films can’t help but note a strong resemblance between The Mad Fox and Kobayashi Masaki’s classic 1965 fantasy movie Kwaidan (Kaidan), released less than three years later.3 This is somewhat ironic, as the Kobayashi film has been widely regarded as a masterpiece since its initial release, whereas the Uchida film, when its existence has been noted at all (for example, by French critic Georges Sadoul),4 has been mostly dismissed, until recently, as a curiosity.

It seems inconceivable that Kobayashi wasn’t influenced by the Uchida film. In fact, one of Uchida’s most impressive visual effects – the floating tongues of flame representing the presence of the world of the fox-spirits – is re-used in an identical fashion in Kwaidan, where it was widely perceived (at least in the West) as a new and fresh visual device. Though I’m a great fan of Kwaidan and of Kobayashi’s work in general, that film’s reputation as an original achievement needs to be seriously questioned in light of the older film.

In this bizarre film – Uchida’s most stylized work – the director’s playful treatment of the narrative’s theatrical elements intentionally fails to conceal the grim truths about power, violence and class oppression at the story’s core.

366 Weird Movies (Geoffrey Smalley)

All the Anime (Jeremy Clarke) [focuses on the animators who worked on the film]

Blueprint: Review (David Brook)

Comicon (Rachel Bellwoar)

Criterionforum.org (Chris Galloway)

DVD Beaver (Gary Tooze) [includes screenshots]

Eastern Kicks (Wally Adams)

Medium (Remy Dean)

Reel Film Reviews (David Nusair) [a rare negative review]

Slant (Bud Wilkins)

Biennial Channel (YouTube) “Venezia Classici Restauri” (Video from the 75th Venice Film Festival (2018), of the Q&A following a screening of the film, with presentation in Italian and English.)

[…] additional notes on Uchida’s ongoing interest in animation, see my review of The Mad Fox, another film in which animals turn into humans and back […]

[…] The Mad Fox Aug 14, 2021 / 8:06 am Reply […]