Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from page 1)

Although during his eight-year sojourn in China, Uchida made no films, he was far from idle. In the latter years of his stay in Communist Manchuria, during the early postwar era, he taught the editing techniques (montage theory) of the great Soviet masters, Eisenstein and Pudovkin, to young Chinese and North Korean film students, who were thrilled that a filmmaker of Uchida’s stature was instructing them. But as every teacher knows (and I can attest to this), it is often the instructor, not the pupils, who gains the most from the exchange of knowledge. And it wouldn’t surprise me at all if teaching these courses rekindled the excitement Uchida must have felt as a young man, when he experienced the silent masterpieces of Soviet Cinema for the first time as an audience member.

I frankly don’t know how the Rebellion from Below project was initiated – whether it was Uchida’s idea or the scriptwriter’s, or somebody else’s concept. But I would like to think that it was an attempt by Uchida himself to emulate, in a Japanese context, the kind of revolutionary cinema that the Soviets had excelled in during the 1920s and early 1930s.

If so, this was a gutsy move on his part. The movie was released during Japan’s Red Scare, when any expression of Leftist sentiment was regarded with suspicion, and after Uchida himself had become ideologically “tainted” by his association with Communist China. And so it was a shrewdly pragmatic decision to set his narrative during the Bakumatsu, a rebellious era with which the right-leaning postwar Japanese government could nonetheless find no fault, as that long-ago political upheaval had led directly to the founding of the modern Japanese state.

Throughout this film, Uchida pursues visual strategies that are not so much imitative of the films of the Soviet Cinema’s Golden Age as deeply suggestive of their inventiveness and power. In one scene, which depicts a conference of the peasants (Teruzo, who’s still in prison, is not present), Uchida unusually places the character who’s the focal point of the scene – the village headman, Tatsuemon – not in the center of the composition, but off to one side at the right of the frame.

This may appear to be a small detail, but it was a new way of organizing such a scene at the time. The novice Toei director Kudō Eiichi, later to achieve distinction in the 1960s (e.g., Thirteen Assassins (Jūsannin no shikaku, 1963)), was inspired by Uchida, according to his biographer (as mentioned in the article I’ve linked to), to experiment with composition in a similar way in his own films.

A memorable swordfighting scene takes place at night, when the rebels take the battle to the enemy, invading the tyrant’s residence to resist Waki’s oppression. The viewer sees the encounter as a fight by figures in silhouette, so it’s difficult to tell who is who. This scene reminds me of how effectively Uchida employed darkness in his prewar movies, Police Officer and Earth especially, and it’s impressive that here, as an artist in late middle age, he is still experimenting with intriguing effects of light and shadow.

Like most of Uchida’s films, this one begins as a drama of male antagonists, but in the second half of the narrative the focus shifts to Waki’s female victims. The deputy governor has just imprisoned Tatsuemon, as well as the rebel father of an innocent young woman, Tsuruno. Waki is thus able to blackmail Tsuruno into distributing a forged letter, allegedly from Tatsuemon, calling the rebels to a meeting. The men take the bait, and when they arrive at the meeting place, they are, of course, promptly arrested by Waki’s men. Tsuruno is shamed and shunned by the village women for her (reluctant) treachery.

Tsuruno then resolves to restore her honor the only way she can, by committing suicide. The scene in which she walks into a lake to drown herself is clearly influenced by a similar sequence in the masterpiece film Sansho the Bailiff by Mizoguchi Kenji, released just two years prior. Uchida’s scene though, it must be admitted, lacks the impact of the corresponding one in the earlier work. For one thing, Mizoguchi’s movie is ultimately the story of a brother and sister, Zushio and Anju, and it is Anju who kills herself, while within the later film, Tsuruno is a much more peripheral character. And of course, Anju was played by a great young actress, Kagawa Kyoko (later appearing in Uchida’s The Outsiders), who made the character’s decision to take her life utterly, heartbreakingly believable, while the actress who portrays Tsuruno is far less effective.

Nevertheless, Tsuruno’s drowning scene has its own haunting beauty. We see the character, utterly calm and fully dressed in traditional kimono, stepping into the water, flanked by two pillars. The space between the pillars functions as a kind of gateway through which the character will enter the next world. In this way, she expiates her “sin.” And it is ironically this death – which the village women themselves, with their repudiation of Tsuruno, helped bring about – that will spark the final uprising.

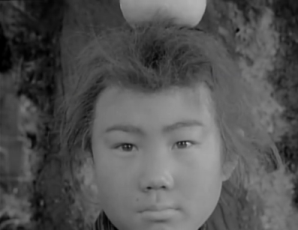

Like the contemporary left-wing American movie, Salt of the Earth, Rebellion from Below highlights the role of women in a political revolt. Mourning Tsuruno’s death, and galvanized by the enslavement of their men, the peasant wives form a kind of ghost army and, wearing sedge hats and armed with farm implements, march in the pre-dawn darkness towards Waki’s fortress. The shot is made more, not less, effective by the fact that we can’t quite see the women’s faces: their anonymity gives them an unsettling power, which will make them formidable foes of the tyrant.

In the heat of any revolutionary moment, the people involved do not, of course, know how the conflict is going to turn out: whether the oppressors or the oppressed will prevail. But the 20-20 vision of historical hindsight gives us as film viewers knowledge that the participants in the chaotic real-life events did not and could not possess.

Thus, Uchida, with that rearview-mirror wisdom, has the right to make of his fictitious rebellion (itself set within an actual historical transition) an entirely joyous experience, a celebration of liberation. Bloodshed is therefore downplayed, and revolution itself is turned into the ultimate festival, a kind of dance. This celebration has its sexual aspect, as when the wives are gleefully reunited with their freed husbands. Uchida reveals to us here that the political tension that had been building in the earlier scenes was also an erotic tension that now finds release, and perhaps it is the very power of that erotic energy that makes the peasants’ victory over Waki’s forces inevitable.

Waki, conversely, is reduced to impotence, as he is humiliatingly made by the peasants to flee, with his subordinates, in a tiny boat without oars, forcing them to paddle away from shore with whatever comes to hand. Rather than chase after them, the peasants laugh at their discomfiture, with the shirtless Teruzo – now the mere symbol rather than the leader of the uprising – laughing loudest of all.1

In the film’s final moments, the peasants, with a mighty effort, pull down a wall of the never-to-be-completed fortress. Though of course, Rebellion from Below was far from the director’s last film, this shot for me stands as the final symbol of Uchida’s legacy as an artist: the tearing down of artificial barriers between individuals and social classes, between film genres, between even comedy and tragedy.

Engaging and inspiring, this drama, loosely based upon Schiller’s venerable classic, displays to the full Uchida’s talents for suspense, characterization and action, with a rousing and satisfying climax.

Blog of a Nostalgic Old Man – This Japanese blogger praises Uchida for his “profundity” and includes favorable reviews for both The Kuroda Affair and this film, which he particularly praises for the “dynamic” concluding scene of the peasant uprising. (English translation by Google Translate.)