Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Other Titles: Counterattack at the Prison Gate Fortress, Counterattack at the Prison Fortress (literal English titles)

| Production Company | Toei Kyoto |

| Scenarist | Takaiwa Hajime |

| Source | Wilhelm Tell [William Tell] (1804 play) by Friedrich Schiller (uncredited) |

| Planning | Tamaki Jun’ichirō |

| Cinematographer | Yoshida Sadaji |

| Art Direction | Suzuki Takatoshi |

| Music | Fukai Shirō |

| Sound Recording | Tojo Kinujirō |

| Performers | Kataoka Chiezō (Teruzo), Ueki Motoharu (Jirō), Tsukigata Ryūnosuke (Waki), Susukida Kenji (Tatsuemon), Takachiho Hizuru (Princess Misuzu), Itō Hisaya (Tatsuma), Yashioji Keiko (Tsuruno), Mori Kikue (Fuku), Kataoka Eijirō (Yaichi), Ehara Shinjirō (Senkichi) |

| Status | Extant |

| Photography | Black and white |

| English Subtitles | No |

| Original Release Date | June 28, 1956 |

| Length | 94 minutes |

| Festival/Retrospective Screenings | None on record |

Google translation of Japanese plot summary at https://eiga.com/movie/35913, lightly edited:

“The conflict between loyalists [of the emperor] and supporters of the shōgunate is intensifying during the upheaval of the late Edo period [mid-19th Century]. Ueryosuke, the lord of the Goshu Nozawa domain adjacent to the Tenryō [i.e., the shōgunate’s estates: literally, “the Emperor’s lands,” as later, during the Meiji period, these lands were returned to the Emperor], wants to support the imperial loyalists, but fears oppression from the shōgunate. He sends his daughter, Princess Misuzu, to Kyoto in the company of Tatsuma, the son of the priest Hirata Nobutane, who is loyal to the emperor, to let the Imperial Court know of their suffering.

The newly appointed deputy governor of the Tenryō, Waki Gundayu, becomes the target of the people’s resentment for his harsh collection of taxes in order to support the financial situation of the weakened shōgunate. One day, he sees Tatsuma and Princess Misuzu trying to reach Kyoto via a secret route, guided by the hunter Teruzo. He keeps quiet at the time, but he soon imprisons Teruzo, using Teruzo’s son Jirō’s carelessness as a shield. Waki also begins building a fortress on the orders of Kyoto’s protector, Itakura, to use the Tenryō as a base to block the eastern expedition [of the imperial forces]. The people are forbidden to enter other territories, and those who are rounded up, like Teruzo, are forced to do hard labor.

Caught between the people and Waki, the village headman Tatsuemon appeals several times to the deputy governor, to no avail, and Waki captures Nobutane and Princess Misuzu as bait to keep the Nozawa clan on the side of the shōgunate. Waki further deceives Nobutane’s daughter Tsuruno, using her to distribute a forged circular letter, allegedly from Tatsuemon, calling for a meeting of the people. At the meeting, Waki captures Yaichi and other young people who had gathered to meet Tatsuemon, and sends them to a remote island.

The people of the domain storm into Tatsuemon’s house, believing him to be a traitor, but through the suicide note of Tsuruno, who had killed herself by drowning out of remorse, they learn of Waki’s insatiable cunning. The anger of the weak, suffering under oppression, explodes. The people of the domain, united under Tatsuma’s command, at the sound of a bell as a signal storm into the deputy governor’s mansion. Teruzo and his men, who have received the news from his son Jirō, break out of the prison and rush to the mansion.

The officials are overwhelmed by the power of the people, and Waki barely escapes with the protection of his subordinates, Tonomura and Segawa. The laughter of Teruzo and his friends as they see off the defeated group of officials, who are fleeing in a small boat, rings out loudly, and once again a bright, quiet dawn has come to their town.”

Note: All screenshots used in this and other posts on this website are reproduced under the Doctrine of Fair Use, and are intended for educational purposes only and not as a substitute for the actual experience of viewing the films themselves. The author receives no profit from this website.

Note: This review is being posted on this website on June 28, 2025, the 69th anniversary of the film’s Japanese premiere in 1956.

It is with great pleasure that I conclude my collected reviews of the surviving films of Uchida Tomu on a high note, with one of the finest films of his mid-1950’s period. Unlike IUTAS member Akasaka Daisuke on our Member’s Page, I would not (quite) refer to this film as a masterpiece, but it is one of the few films I know that successfully depicts a revolutionary uprising.

It should be noted that the movie transcends the historical moment it dramatizes, as it doesn’t really support either the imperial side or the shōgunate in the conflict. Rather, it shows the people collectively taking matters into their own hands and assuming responsibility for their own future, rather than depending on some far-away sovereign to do it for them.

Appropriately, Kataoka Chiezō, as the humble hunter Teruzo, portrays a very different character from his usual type, as exemplified by the counselor Daizen in The Kuroda Affair, the sage upholder of samurai tradition. One might similarly claim that his role as the spear carrier Gonpachi in A Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji was a bit of casting against type, as he didn’t play an actual samurai in that film. However, as a samurai’s servant, Gonpachi is very much part of that world and has assimilated its values and moral code.

But Teruzo, the hunter, is entirely separate from that world and, for that matter, from the world of the imperial court. He and his young son, Jirō, thus stand completely naked before the ruthless and arbitrary power of tyranny, as symbolized by the shōgunate’s evil magistrate, Waki. His only allies are his fellow sufferers among the people and their aristocratic allies, Tatsuma and Princess Misuzu – but this spontaneous alliance turns out to be more than enough.

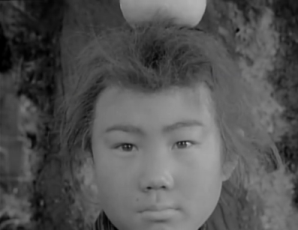

The script’s most obvious borrowing from its (uncredited) source, the early 19th Century play Wilhelm Tell [William Tell] by Friedrich Schiller,1 is the scene in the play depicting the legendary incident in which the marksman hero is forced by a tyrannical official to shoot an apple off his young son’s head. In the film, however, this is not the first confrontation between the evil official and the hero. Teruzo with his son Jirō in the very first scene had hunted in the snow and killed a wild boar that Waki’s hunting party, present in the area at the time, also claimed. In the end, Waki resolved the dispute by letting Teruzo keep the dead animal, but he insultingly shot it anyway, perhaps as a sign that the boar – indeed anything on the shōgun’s land – was really his, and that a mere hunter like Teruzo had no right to claim it, or anything else. Teruzo’s humiliation was compounded by the fact that his son witnessed all this.

Not content with having degraded Teruzo once, the sadistic Waki decides to challenge the hunter a second time. When the hot-headed Jirō disrespects the Tokugawa hollyhock crest2 that one of Waki’s underlings had displayed publicly as a test of the people’s loyalty, Teruzo begs that his son be pardoned. Waki decides to forgive him only if he can prove his marksmanship by shooting an apple (actually, a Japanese persimmon) off his son’s head. Not only is he then forced to risk his son’s life, but he would forfeit his own life if he misses, even if the son survives.

In response to this outrageous order, Teruzo doesn’t act like a hero in a Hollywood movie, but like a terrified, ordinary man of any place or era. He begs and pleads with Waki, but the magistrate is immovable. He next appeals to the other farmers, who are witnessing this confrontation, but they are as frightened as he, and refuse to offer him solidarity. Ironically, the child remains the eye of the storm in the scene, calmly urging his father to go ahead and make the shot, and expressing his faith in him.

As Akasaka Daisuke notes, the entire sequence plays exactly like a stage scene, yet it doesn’t feel “stagey.” At the turn of the 1920s, a new tendency in cinema dubbed the Pure Film Movement (jun’eigageki undō), championed by young film fans and critics, had urged Japanese filmmakers to make movies that were less like theatrical performances and more like Hollywood films. These enthusiasts didn’t want Japanese films to sacrifice the pleasures of cinema to the conventions of its stage traditions.

In this work, we see Uchida – whose own career had begun during that earlier, groundbreaking period – taking these lessons to heart, creating a well-thought-out sequence that totally works as cinema, with a dynamic use of screen space. At the same time, the sequence also works as theater: the antagonism between the main characters couldn’t be starker, there’s a clear dramatic progression, and the suspense is terrific.

So when Teruzo finally shoots and hits the bulls-eye precisely – the look of amazement on the boy’s face is priceless – the viewer experiences both a theatrical and a cinematic catharsis. However, Waki then double-crosses Teruzo and arrests him anyway. The dramatic problem introduced by this clash of wills thus can’t be resolved by Teruzo alone, but rather by the people collectively.

(Continued on page 2)