Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

(Continued from page 1)

The style, tone and themes of this film are subtly but unmistakably different from Uchida’s highly successful five-part Toei series of Musashi films (1961-1965). Unlike most of the locations for the original series, the single location for this film, a weedy, mist-covered field in the mountains, described in a subtitle as “Urin’in Village in the Suzuka Mountains,” does not really appear Japan-specific: we could be literally anywhere on earth. And though the narrative starts out as a more or less realistic (though very strange) action drama, the narrative turns increasingly symbolic, even allegorical. It’s a unique film, even in the context of Uchida’s incredibly diverse filmography.

It should be noted that, even if we accept as plausible the characters’ eccentricities, such as Omaki teaching her infant son to overcome physical fear by twirling a ball and chain within inches of his head, many plot details are, to say the least, improbable. By what moral logic do Baiken and his wife seek revenge on Musashi for killing her brother at the Battle of Sekigahara, since in war killing the enemy – which, from Musashi’s point-of-view, the brother certainly was – is exactly what one is supposed to do? And in any case, how could Baiken and Omaki even have known that it was Takezo (that is, Musashi) who killed her brother in the first place, given the general anonymity of killing during any battle, particularly a battle as big and important as that one?1 Why does the intelligent Omaki simply assume, during the night, that Miyamoto is really asleep and not feigning (which in fact he is)? Why do Baiken and his men plot Miyamoto’s death right outside the hut, where their voices if not their words can easily be overheard by their intended victim?

However, I don’t think Uchida had suddenly turned into a sloppy storyteller. Rather, he was adapting this material for a purpose for which plot logic was ultimately beside the point. This is indicated by his use of the striking “freeze-frame” device, in which the film literally stops dead to allow the viewer to “eavesdrop” on the characters’ thoughts via voiceovers. These don’t add much to our understanding of the characters, but they do create a dreamlike atmosphere to prepare the audience for the bizarre events of the movie’s second half.

Many of the disturbing aspects of the Musashi character – the dark subtext of the earlier Toei series – are presented here unfiltered. To put it bluntly, if Musashi is a hero, who needs villains? Uchida seems to have intended the viewer to look upon the samurai as a good guy because, when he enters Baiken’s hut and sees the child Taroji, he smiles at the baby in a kindly way. But there are doubtless many adults who feel no particular affection for children, or who even dislike being around them, but nonetheless would never dream of harming one. Yet Miyamoto – without moral qualms and, indeed, cheerfully – exploits the baby as a pawn in his deadly battle with Baiken and Omaki.2 If Baiken had accidentally killed the baby in his attempt to destroy the samurai, but Musashi himself had survived, he would surely not have slept any less soundly. This is the very definition of a sociopath.

In fact, the viewer’s sympathy in the latter half of the movie shifts abruptly from Musashi to Omaki. She not only displays all the filial devotion her husband lacks, but, sacrilege of sacrileges, she’s willing to place the rights of the living (the baby) above the warrior’s imperative to avenge the dead. And so she fights even more fiercely to save the samurai, for the sake of her child, than she had fought earlier to try to kill him, when only she and her husband were in danger.3

The earlier pentalogy of Musashi films boasted a very large cast of major and minor characters. In Swords of Death, however, though Baiken has a gang of eight members, they’re poorly individuated, and the viewer doesn’t remember them, so their deaths have no impact. Thus, in dramatic contrast to the Toei series, in this movie only four characters matter: Musashi himself, Baiken, Omaki and the infant Taroji.

I deliberately include the baby because the theme of The Endangered Child runs like a scarlet thread through Uchida’s work. As I note on the last page of my biography of Uchida on this website: “Many of [Uchida’s] heroes… have child sidekicks who share their adventures. The brothels of ancient Osaka and Edo [in his films]… are filled with innocent girl-children, preparing themselves to take the places of the adult courtesans. The young daughter Otsugi in Earth is central to the narrative of that film… and a roguish child is the protagonist of The Horse Boy. And it’s sometimes very dangerous to be a kid in Uchida’s world, as proven by the gory death, at Musashi’s hands, of the very young head of the rival Yoshioka clan in the fourth installment (1964) of the Miyamoto Musashi series.” Taroji thus represents an absolute innocence – as opposed to the partial innocent of the child characters cited above – set against the irresponsible violence and corruption of the adult characters (Musashi, of course, included).

For those familiar with Uchida’s personal history, Baiken’s behavior – and to some extent Musashi’s as well – calls to mind Uchida’s former boss, Amakasu Masahiko, whom the director had deeply admired when they worked together at the Manchuria (Manchukuo) Film Association (Man’ei) during the war. As head of that studio, Amakasu treated his employees, including former left-wingers like Uchida, his actresses and even the natives justly and with respect, and after he committed suicide following Japan’s defeat, hundreds attended his funeral. But he had also, as a younger man, brutally murdered in cold blood a loving couple – the anarchist Ōsugi Sakae and his partner Itō Noe – as well as a child, Ōsugi’s American-born nephew.4

Much like Amakusa, Baiken places honor, or rather his perception of it, above any other value, even his duties as husband and father. And since Taroji is his only son, the bandit is prepared to literally throw away his legacy to revenge the deaths of his brother-in-law and his gang. Baiken seems to symbolize the prideful male ego of all times and places, and the fact that he’s also depicted as a loving (though not particularly competent) father shouldn’t be seen, in my opinion, as contradicting this.

It’s very tempting to regard the protracted standoff between the samurai and the bandit couple as a metaphor for the Vietnam War, which was still ongoing at the time the film was made, and by extension the Cold War. Certainly the final scene, in which all the characters are literally surrounded by fire, suggests both hell and some ultimate modern Armageddon, like a nuclear war.5

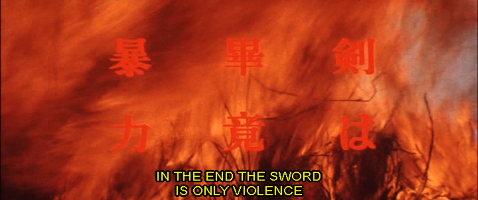

The startlingly “pacifist” final title card – “In the end, the sword is only violence” – represents an unprecedented editorial intrusion by the director into one of his own narratives.6 (However, this is true only if we assume that the insertion of the title card was indeed a creative choice by Uchida himself, which is by no means certain, due to the controversy over whether the film was actually completed according to his wishes.) If the decision was, indeed, Uchida’s, it seems to represent not only a repudiation of the ultranationalism towards which, during the war, he had been greatly attracted, but a renunciation of all violent ideologies, including orthodox Marxism, to which he had also once been attracted.

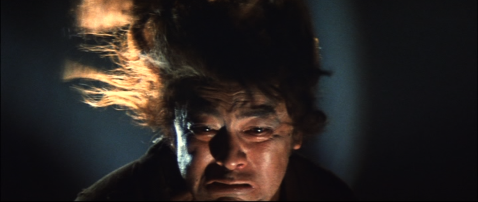

Mikuni Rentarō’s performance as Baiken is extraordinary – though some might claim that it’s extraordinarily bad. If the phrase “chewing the scenery” for an out-of-control actor didn’t exist, it might have been invented for his work in this film. (His performance here contrasts intriguingly with his subtle, natural and layered acting in Uchida’s masterpiece, A Fugitive from the Past, and even with his relatively restrained performance as Takuan in the Toei Musashi series.) The only artistic justification for all his grimacing, glaring and shouting is that Uchida never meant Baiken to be a realistic character, but to transition gradually into a symbolic, even demonic, one.

By contrast, Okiyama Hideko’s performance as Omaki is nothing short of incredible. It should have made her a major star, but, as was the case with Mizutani Yaeko after her exceptional work in Hero of the Red-Light District, nothing really happened to her career as a result of the film, despite the fact that it made the Kinema Junpo Best Ten list (in sixth place) for films released in 1970. Okiyama would not appear again in a film for six years, though that long gap might very well have reflected the demands of her other career as a professional singer.

Uchida probably cast her because of the earthy, even feral, intensity she had brought to Imamura’s The Profound Desire of the Gods, in which she played a highly erotic, “primitive” young island woman. For this film, Uchida seems to have encouraged her to take this primal quality as far as she could go without self-parody. When Omaki implores both Musashi and her husband to spare her son’s life (see featured image above), Okiyama’s plea is so loud and fierce it seems as if all the mothers in the world are crying out at once – which may well have been exactly what Uchida intended. When one considers all the Hollywood actresses who have ineptly, even laughably, attempted to portray fierce warrior women, it’s astonishing how plausible Okiyama is in the role, both as a killer and as a loving mother.

The biggest controversy involving this film – which very few people have seen – is whether Uchida actually completed it. (Roger Greenspun in his New York Times review called it “incomplete,” a claim he may well have repeated from the distributor’s publicity materials.7) There are numerous indications which suggest he didn’t finish it, the most obvious being the fact that the showdown between Baiken and Musashi is left unresolved – an open ending the likes of which Uchida had never offered, as far as I know, in any of his previous surviving films – as well as the movie’s uncharacteristically brief length (75 minutes). However, Suzuki Naoyuki, Uchida’s screenwriter on A Fugitive from the Past, claimed in a biography of the director that the latter lived just long enough to finish the picture, more or less the way he wanted, on June 12th, 1970, about eight weeks before his death on August 7.8 The editing-machine-in-the-hospital-room story to which I alluded above would seem to bear this out.

It would of course require a careful study of the shooting script, any unused footage that survives and any notes Uchida might have left behind to resolve the question of the film’s status as an “unfinished” work.

A typically strange product of Uchida’s final creative period, this work offers an ambiguous but curiously satisfying coda to Uchida’s complex and brilliant career.

New York Times review [Roger Greenspun]

Weird Wild Realm [Paghat the Ratgirl] (This blogger makes some interesting comparisons between the Inagaki and Uchida versions of the Musashi saga)

Barrett, Gregory, Archetypes in Japanese Film: The Sociopolitical and Religious Significance of the Principal Heroes and Heroines (book), pp. 54-56. (Barrett engages in a brief but fascinating discussion of the film, particularly relating to the Sino-Japanese war and to the film’s final title card renouncing violence.) Associated University Presses, 1989. ISBN: 9780941664936

Hi!

I’m a Japanese fan of Tomu Uchida’s films.

I was doing some research on Swords of Death and happened to stumble upon your blog. I was really surprised. Even in Japanese, there are not many detailed articles about this film, so I truly enjoyed reading your thoughtful post.

I have two comments I’d love to share:

1. I totally agree with your point that this movie is an allegorical narrative. To add to that, I think understanding the industrial context of Japanese cinema in the 1970s might also help deepen the reading. At that time, just like in Hollywood, Japanese Studios were rapidly losing their audience as TV and other forms of entertainment were rising. (One of the major studios, Daiei, even went bankrupt in 1971.) It was a period of serious decline for the film industry, but ironically, that decline also opened the door to new creative energy. Filmmakers began experimenting: taking cameras out of the studio, using real locations more boldly… and in a way, it was the low budgets that made those creative risks possible. It’s not hard to see this new creative energy reflected in Tarohji, either. Final shot, a baby smiling in front of a burning field, feels like a totally direct allegory for the circumstance and atmosphere of Japanese cinema in the 1970s. To me, it captures both the destruction and the strange sense of hope that existed at the time.

2. A quick correction. You wrote AMAKUSA Masahiko, but the correct name is AMAKASU Masahiko(甘粕 正彦). Anyway, what the war meant to Uchida himself, I’m on the way of trying to figure that out too.

Best.

Thank you for your kind comments. Your interpretation is very interesting: you accept my premise that the film is allegorical, but you claim it is about the movie industry rather than Cold War politics. Thanks also for pointing out the regrettable error with Amakasu’s name. I have corrected it.